scott b. davis with HereIn

Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1999, platinum/palladium print, 8 x 10 in.

[Image description: A stark nighttime landscape with a black foreground and gray clouds streaking across the dark sky. A thin line of lights glows at the horizon.]

With a distinctively minimalist aesthetic, scott b. davis’s photographs transport viewers into the desert landscape. Employing photographic materials and techniques that date back to the 19th century, the serene, meditative images evidence his deep technical knowledge and formal innovation. davis’s involvement in the San Diego art scene transcends his own work through his involvement with Medium Photo, a non-profit organization benefiting artists, which davis founded in 2012. He spoke with HereIn Intern Ciara Colgan to discuss his work with Medium Photo and the development of his own artistic career.

HereIn: You have said that boredom drives creativity and that the motive of discovery drives your work. Can you talk about the first spark of desire for discovery that prompted your work as an artist?

scott. b. davis: One of the most creative experiences in my life was an attempt to make a photograph at night, at a scenic overlook, which I thought would look like an inky version of what we see in daylight. What ended up happening was a photograph that captured a sea of black and the capitol city of Mexicali, Mexico on the horizon. It was something that fused a lot of concerns I have in my work. Specifically, how the human landscape shaped my interest as an artist and how that interest shaped this early work.

To put it another way, one of the biggest creative drivers of my career was an accident. It was an accident based on my expectations.

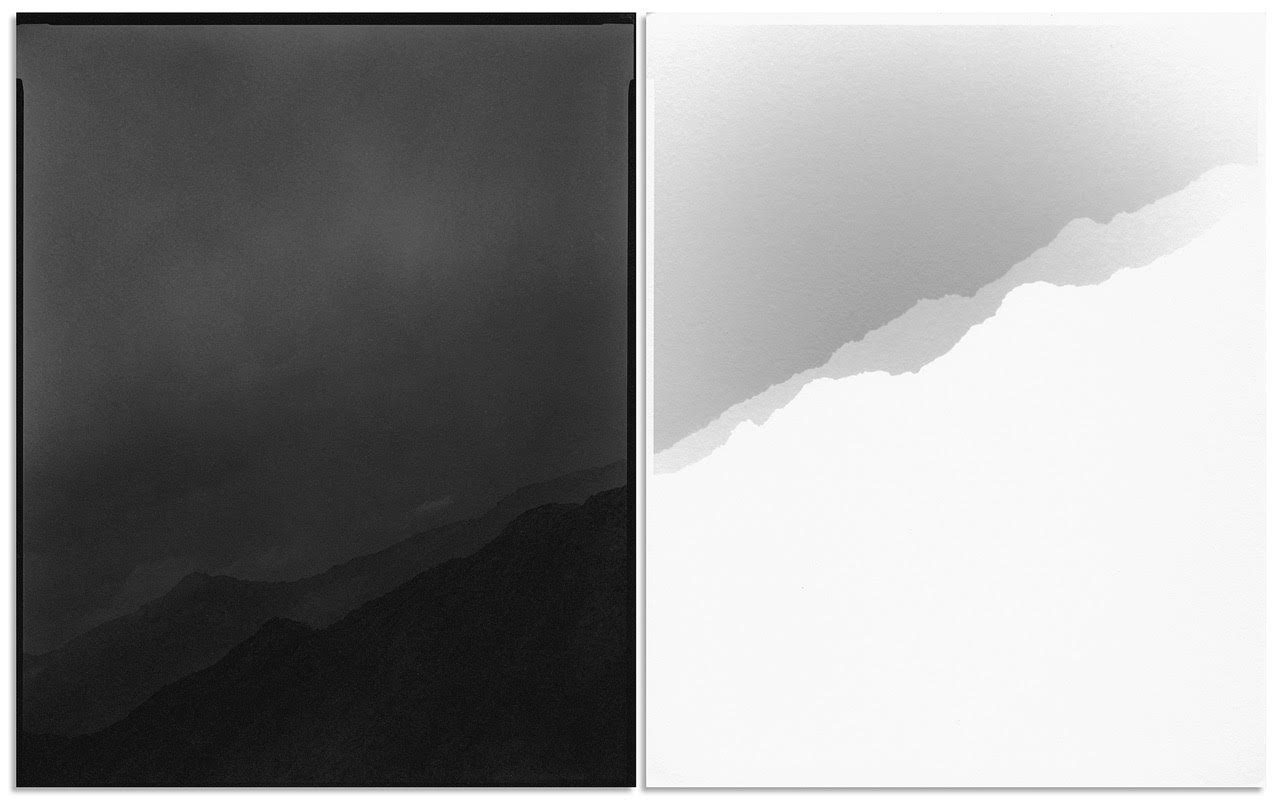

Two Nearly Identical Ridgelines (Canyon Sin Nombre), 2019, two unique platinum/palladium prints, 10 x 8 in. each

[Image description: Two images side by side, the one on the left in black and dark gray, the one on the right in white and light gray. Each depicts the ridgeline of a mountain, so minimalist as to be nearly abstract.]

HereIn: Your cameras and development processes follow photographic practices from the 19th century—what is it about this manual and time-intensive process, as opposed to digital photography, that drew you in?

davis: The draw is really about the act of printmaking. The 19th-century process that I work with, known as platinum palladium printing, is one that has a kind of legendary reputation in photography. When this process was invented, and when it was in regular use into the early-20th century, it was sought out by photographers to print their finest images. The photographs they thought were the most exquisite were the ones they would use the process for. Platinum printing saw a resurgence in photography in the 1970s and 80s, and I was drawn to it because it involved a lot more involvement from me as a user, and it gave a lot more options in terms of output. What I mean by that is the kinds of paper that I can make prints on, the types of chemistry, and the effects that those chemicals have on the final print are tools that I use and that are of interest to me in the process.

Stonehenge, Wiltshire, England, 2002, platinum/palladium print, 8 x 10 in.

[Image description: A nighttime landscape, with the prehistoric monument Stonehenge standing at the horizon.]

HereIn: I noticed that there are no people in your photographs, but many include human-made products such as cities, buildings, or even Stonehenge. Tell me about these choices.

davis: A lot of my process comes from a comfort in working alone. My interest in the human-made landscape stems from the first night photograph that I made and that intersection between how people have shaped the land and how sometimes we need to find space within that land to be alone. Working at night was partially a way to not be around people, and to see landscapes without concern for people asking what I'm doing, what kind of camera I'm using, etc.

The people who ask what kind of film you shoot are akin to somebody asking a painter what kind of brush they use, or a sculptor what kind of tools they prefer. Those questions are really not important to my process and were easily avoided by working at night or in remote places. Because I work with cameras that are unusually large and made of wood, they naturally draw questions from people I come across.

Building, Sunset Strip, 2005, platinum/palladium print, 16 x 20 in.

[Image description: A nighttime shot of a nondescript white building. In the left corner of the image is the side of an illuminated billboard, while a shining lamppost stands to the right of the building]

Thinking about the specificity of your question, places like Stonehenge, things like buildings in Los Angeles, for example, a lot of that came through a process of working in photography with an intention of exploring minimalism. It's the impression or the intention of working in a minimalist way that started to get my mind working on specific ideas about what is shown and what is not shown, and encouraging the viewer to use their imagination in seeing something familiar or seeing it in a new way.

I began making photographs of cities in the desert at a distance. To see an entire city encapsulated in a single photograph is almost incomprehensible because you have millions of people that are reduced to an object that is maybe eight-by-ten inches. It was from there that I started to think about photographing within cities, and specifically it was Los Angeles that was a draw to me.

HereIn: Before you go into the field, do you normally have an idea of what you want to photograph? How do you find the perfect subject?

davis: For the last ten years, I have taken the 19th-century platinum printing process and used it in unorthodox ways. The process is intended to render a photographic negative as a positive, which is true of all analog photography. I began to use these materials inside of a camera as opposed to inside of a dark room with a photographic negative shot on film. I did that to experiment and see what was possible with the medium that hadn't been thoroughly explored historically.

Ocotillo, Santa Rosa Mountains, 2013, unique platinum/palladium print diptych, 20 x 32 in.

[Image description: An image of a spiky ocotillo, divided down the center. On the left, the plant and the ground are in white, while on the right they are in gray.]

But, I guess, in answering that question, I've moved in my practice from the traditional photographic pursuit, which is going out into the world to look for something that can be extracted as a rectangle and made into a photograph. Because I've been working with photographic negatives as a finished product, and I've been working with levels of abstraction as a finished product, I've stopped photographing or making art in the way that photographers typically operate. I've started to simply use my imagination and drawing as a tool to envision what it is that I want to make a picture of, and then going out into the world and finding that. As an example, I was photographing in Joshua Tree over the last four days, and well aware of what a Joshua tree looks like. Because I know that landscape well, I spent time in advance sketching the kinds of works I would want to make that don't necessarily fit a representational mode. I then go out into the world in a traditional photographic mindset and look for subjects that fit what it is that I've sketched out and what it is that I'm hoping to render.

HereIn: You have mentioned that the connections you have made with other artists have helped you throughout your career and artistic journey, which motivated you to start Medium Photo. Can you talk a little about this nonprofit and how it has further promoted community among artists in San Diego?

davis: Medium Photo is an organization that gives a platform for contemporary artists to talk about their work and to expand their ideas on photography. We do that through educational workshops and artist lectures. The organization started from a lack of similar programming in photography in the binational region we call home.

Artist lectures and educational workshops were two of the most foundational experiences that shaped me as an artist. I know I'm not unique in that way, and I wanted to offer the same kinds of experiences for other artists in the community. One of my primary goals in starting Medium Photo was to get artists and collectors to travel to San Diego from Los Angeles. That meant creating programming that wasn't available in Los Angeles or programming that was unique enough to draw people from LA. In Medium’s first year about fifty percent of our audience came from Los Angeles, with other attendees from eight states and the greater San Diego region. To provide that kind of programming here in San Diego is an asset for artists in our community because it means that cutting-edge thought is brought to our doorstep without needing to travel elsewhere or watch content online. Our keynote speaker from 2023 was just hired to run the photography department at Gagosian in New York. It's a great example of the kind of people we bring to San Diego, sharing ideas that exist at the cutting edge of the art world.

This conversation has been edited by HereIn and the artist for length and clarity.