Kanthy Peng with HereIn

Surf Cam, 2023, livestream video and aluminum sheet, 34 x 40 in.

[Image description: An image—in the shape of a car side mirror—of two people watching the sun set over the ocean.]

Drawing equally on historical fact and ghostly folktales, Kanthy Peng’s lens-based practice examines the mobility that results from colonialism, natural disasters, and global tourism. She spoke with HereIn Editor Elizabeth Rooklidge about her recent exhibition at San Diego gallery Best Practice—her first in California— which featured works that explore the dynamics of seaside life.

HereIn: Your career has truly been an international one. Where are you from originally and what has your trajectory looked like?

Kanthy Peng: For me it’s really been about not finding a place to stay stable, you know? I still don’t have a green card. I was born in China, in Beijing. I studied art, both undergraduate and graduate, in the U.S. While in grad school I decided that I maybe wanted to stay here longer, but it’s really hard for an international artist. Even for U.S. artists, it’s really hard— there aren’t that many opportunities, you have to apply everywhere. So that’s why I’m traveling. I’m not opposed to going places, it’s just that now I have a dog. [laughs]

HereIn: I’d love to dive into your work. What would you say are the primary questions that drive your practice?

Peng: If there’s a primary question, I think it’s this idea of how I use image-making to tell stories. That includes a lot of different perspectives. Like, why do we still need to make a new image today? There are tons of images and people no longer have belief in photographs anymore. So why image-making? Another is what kind of story I want to tell that feels original and why people bother to hear anyone’s story. What are the expectations of it? And what are the ways you might be able to break those expectations?

Sunset Watchers, 2023, archival inkjet print on Moab Metallic Pearl with aluminum floating frame, 8 x 10 in.

[Image description: A framed, black-and-white photograph of a woman standing with her hand on a rock, looking longingly out to her left.]

HereIn: You tell a lot of different kinds of stories. How do you choose which ones to tell?

Peng: Many of my recent works are about folktales in East Asian culture, specifically in China and Japan. I’m really interested in folklore as a way of telling stories that is not controlled by the government or by history— everyone can tell their own version of folktales. I think that has a lot to do with the similarities between how folktales circulate and how images circulate.

For example, the recent work I showed at Best Practice— the three small portraits of women— are a reflection of a Japanese folktale. And another work, called Another Awaiting Stone, which I made between 2017 and 2020, that’s based on a folktale from China. Both of them have a female protagonist who is very tragic and I want to explore why it’s always this tragic female figure that carries the weight of these stories.

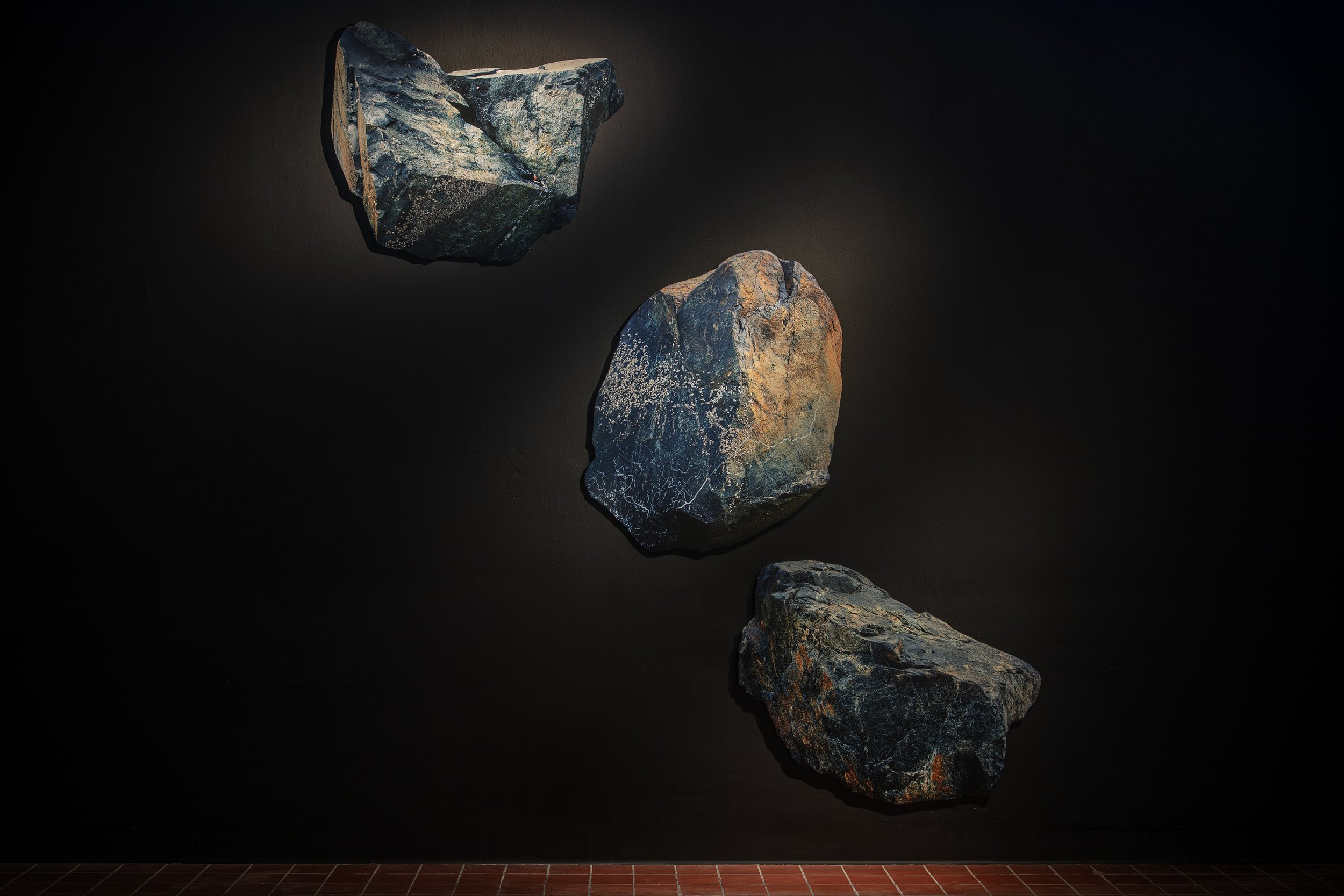

They Won’t Go, 2023, archival inkjet print, Moab Metallic Pearl, and gelatin silver print, 44 x 44 in.

[Image description: Three images of boulders hung on a black wall, arranged as if they are tumbling down to the ground.]

HereIn: It’s interesting to think about that in conjunction with another work you had at Best Practice, the boulders— that imagery comes from a specific historical event in San Diego. How did you become interested in that story?

Peng: I moved to San Diego last year with my wife. I‘m always curious about the ghost stories in different places, so the first thing I researched after I came here was ghost stories in San Diego. It led me to the Hotel del Coronado. They have a very famous ghost story— it’s this visitor, also a female, who checked into the hotel but never left. People were trying different methods to find her ghost in the hotel. So I went to the hotel and I was interested in why you would want to build a hotel somewhere so close to the ocean. In his book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh raised the similar question “But haven’t people always liked to live by the water? Not really. . . it was not till the seventeenth century that colonial cities began to rise on seafronts around the world.”

My wife is a big surfer. I always had to drive her to the beach and wait for her until she finished her surfing. For me it looks kind of scary. Like, why would you want to do it? It’s not something I would do. I believe there’s a death drive in this act, which can be beautiful in a way. It also has this personal perspective, me waiting in the car, waiting for someone that engages in this activity, surfing, so often. And what that stuff can mean, like, this feeling, whether it’s being scared, or confused, or jealous, almost.

I started doing some research about why Elish Bakcock, Jr. and Hampton L. Story chose to purchase Coronado island and to have the hotel built here, and found out that forty Chinese immigrant workers were transported from San Francisco to San Diego to participate in this project, building this hotel. But they were not documented. Whose names are recorded in the history of a magnificent project like this one is important, but those who were not recorded is also a form of archive, an archive of absence.

There was a harbor project in front of that hotel, where they transported these giant rocks and tried to build a harbor but abandoned it halfway. The giant rocks in the gallery that I photographed were a representation of those rocks. The proximity between transporting a group of people/labor and transporting the rocks interests me.

Surf Cam, 2023, livestream video and aluminum sheet, 34 x 40 in.

[Image description: An image—in the shape of a car side mirror—of two people watching the sun set over the ocean. It hangs in a darkened gallery space.]

In the Best Practice show there was also a floating projection in the shape of a car window. That was a livestream of a surf camera. I had always wanted to make images of people waiting for a sunset, and then one day I realized that there are already tons of livestream cameras capturing people waiting for a sunset in front of the ocean. These people are looking for something that’s far away, but not quite knowing exactly what is going to happen. A sunset, a future, a past. So I think, “Okay, there’s no need for me to make another image like that, I can just livestream what reality looks like.”

This is the first time I’ve lived somewhere so close to water, so that for me feels very significant and impactful. I spend a lot of time staring, curious about what people are thinking when they are watching the ocean. I have a fear, which might not be accurate, that it’s a place where disasters could happen. I want to understand what my mentality is and how other people who live here process that.

HereIn: What you’re saying reminds me of this idea of the sublime, this mix of awe and fear. Your work is all aesthetically very beautiful, but the way it was installed at Best Practice, there was this palpable sense of dread.

Peng: That was most apparent in the giant rocks that, instead of having them on the ground, I had on the wall. I wanted them to feel like they were falling, and really make people feel small. Also the small portraits of the women, I call them Sunset Watchers, I wanted them to have that unsettling feeling— through the lighting, the black and white color scheme, and their facial expressions. To make people feel that they’re approaching something, waiting for something, but also trying to escape and are not able to because they’re trapped in this small, eight-by-ten frame.

HereIn: That strategy was very effective. What else are you excited about exploring in your work during your time in San Diego?

Peng: I hope to extend this project to make multiple mirrors and projections that have live streams of different locations, different beaches around the world. I envision that while I’m watching the sun rise in San Diego, some place is having the sun set. I also want to do more works about this idea of distance. San Diego has a very close latitude to Japan, where they’ve had tsunami disasters before. I want to imagine these tragedies, folktales, and ghosts circulating while the waves are circulating. Like these are two locations on two sides of the Pacific Ocean, the connections are very obvious politically but there are also these underlying connections that I want to explore. Can the ocean teach people to speak the same language and help them understand each other, or is that just an illusion?I think the Sunset Watcher portraits are a starting point. If there are any folktales in San Diego, I might bring those to Japan, too.

[This conversation has been edited by HereIn and the artist for length and clarity.]