Dillon Chapman on Nathan Storey

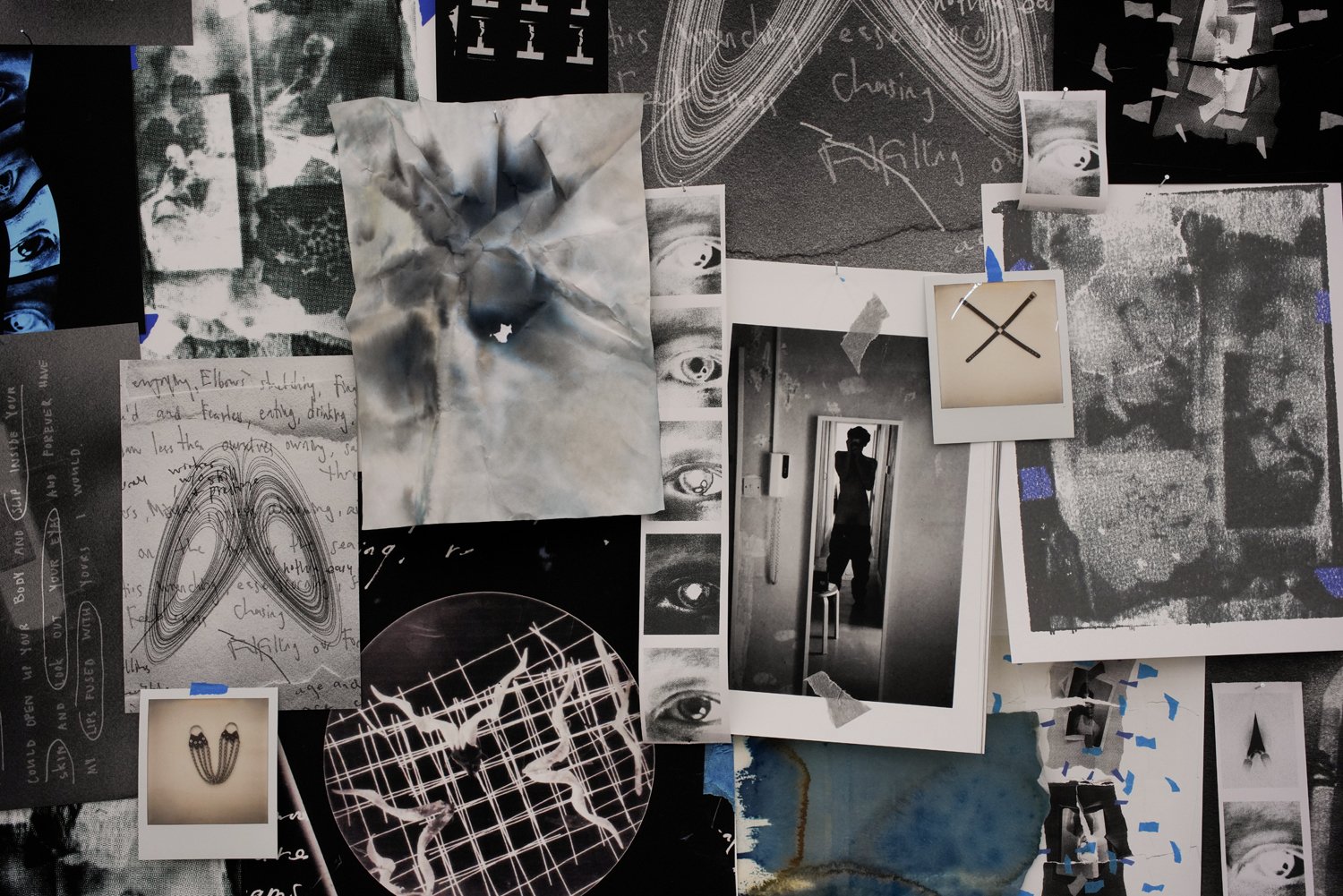

Trace 01, 2023, wall collage consisting of contact prints, positive and negative pigment prints, cyanotype testing stains, xerox prints, thermal prints, manipulated transparencies, polaroids, and blue tape, dimensions variable. Photo: Wren Gardiner

[Image description: A wall collage consisting of overlapping images, mostly in black and white, faded grayscales, and monotone blues. Words, bodies, and cultural symbols are discernible.]

Over the past several years, I’ve observed a growing movement within visual art that I would call a “Queer Pictures Generation,” and a particular preoccupation with queer, trans, and gender-expansive archival materials, especially photographs and periodicals. Artists are moonlighting as historians and archaeologists as a way of making sense of their own subject positions, and how they fit into larger cultural frameworks and legacies. To understand what I mean by a Queer Pictures Generation, I should first contextualize the Pictures Generation, which is generally understood as:

… a group of American artists who came of age in the early 1970s and who were known for their critical analysis of media culture… Inspired by philosophers such as Roland Barthes, who had questioned the very idea of originality and authenticity in his manifesto The Death of the Author, this loose-knit group of artists set out to make art that analysed their relationship with popular culture and the mass media. [1]

Artists in this group include, but are not limited to, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Sherrie Levine. While the methods used by these artists have been widespread over the past several decades, this Queer Pictures Generation has a particular shared sensibility, which unites the work in ways that are not always instantly recognizable. It would be impossible to pin down a specific origin point, however the most visible artist that I would include in proximity to this group is Paul Mpagi Sepuya, but I would argue that he is perhaps more a predecessor to this movement (akin to John Baldesaari and the Pictures Generation). Other artists I consider to be part of this particular movement are Pacifico Silano, Hank Ehrenfried, Jessica Buie, Steven Hector Gonzalez, and Nathan Storey, whose work this essay will explore in depth. I believe that this fascination with various queer archives is, at least in part, a result of the AIDS crisis, a genocide of neglect that robbed a generation of queer, trans, and gender-expansive people of their peers, and another generation (and subsequent generations) of their elders.

With these holes in queer histories and culture, this apparent preoccupation with permutations of the queer archive should not come as a surprise. Of course all of these artists work with different material and content, from Sepuya’s meticulously staged and captured images, to Ehrenfried’s paintings of homoerotic photo collages. Silano’s re-photographed images use pre-AIDS- era gay pornographic magazines as source material, and Buie’s recent photo collage works are carefully curated and re-photographed, exploring depictions of womanhood in popular culture. Gonzalez’s project Broken Icons mashes up gay pornographic icons from various periods, from Tom of Finland to contemporary gay porn studios, held together by blue tape and then printed. I take such care to contextualize Storey’s work with these other artists because I see his as part of a movement and in conversation with these other practices. While all of these artists work with images, and to some extent photography, Storey’s work is concerned with the print, not the capture. It is not the act of photographing, but in the printing of the images that Storey finds the work within his process.

Nathan Storey (b. 1995), originates from Southeast Texas, and is a current MFA candidate at the University of California San Diego in the Visual Arts Department. His art practice, as articulated on his website, “deals with sexuality, memory, and American culture. His current research investigates queer traces, fragments, and stains. Through play with pictures, poems, journals, found objects, and ephemera, the work tangles a boundless relationship between memory and desire.” Storey’s most recent work, which comprises several overlapping and intersecting projects, deals with notions of queer histories and loss. The idea of the archive is often treated with reverence, but Storey’s work is decidedly irreverent, which positions it as a queering of the archive. This archive is organic, accumulative, and about searching. Searching for something unknown (and possibly unknowable) that has been lost. I return to Julietta Singh’s book No Archive Will Restore You, in which she points toward the understandable, yet futile desire to attempt to reconstitute oneself through an archival impulse. Storey is not piecing things back together, he is combining and rearranging things, through which images, ideas, traces, or stains, are both concealed and revealed. Ultimately, one thing is for certain: this is not an intended autobiography, but rather a contribution to pre-existing and imagined archives.

Trace 01 (details), 2023, wall collage consisting of contact prints, positive and negative pigment prints, cyanotype testing stains, xerox prints, thermal prints, manipulated transparencies, polaroids, and blue tape, dimensions variable. Photos: Wren Gardiner

[Image descriptions: Detail shots showing a wall collage consisting of overlapping images, mostly in black and white, faded grayscales, and monotone blues. Words, bodies, and cultural symbols are discernible.]

To give a holistic sense of Storey’s practice, I will examine three distinct bodies of work, the first of which is titled Trace 01 (2023). This work is an assemblage of various print methods and subjects: a temporary collage of sorts. Included are contact prints, positive and negative pigment prints, cyanotype testing stains, xerox prints, thermal prints, manipulated transparencies, and polaroids (I see here an echo of visual strategies used by Lyle Ashton Harris, and more recently Elle Perez). Those are the materials that we are presented with, which, at first, overwhelm the visual field of the viewer. The subject matter is both discreet and discrete, and consists of layered self-portraits, field notes, pictures of lovers, recorded notes on Félix González-Torres, David Wojanarowicz, Herve Guibert, and ACT UP. When listed out it is easy to draw connections between these seemingly disparate traces. The through lines are queerness and the AIDS Crisis. There is a searching for a gay legacy, a legacy interrupted/intersected by the mass loss of queer people in the 80s and 90s due to the intentional neglect and malice of a government and populace with a deeply held animosity of queerness and gender variance: a welcomed genocide. The continuing accumulation of these various prints is about this process of searching, and a searching that doesn’t have a predetermined end - the ending itself may never be reached: there is no wholeness, only disintegration. The most striking elements of the wall collage are the Muybridge-esque prints of Félix González-Torres’s Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform) (1991), the (at times indecipherable) texts, the bits of blue that pop up in polaroids, tape, and transparencies, and the self-portraits that do not necessarily read as such - it is not paramount that a viewer understand Storey’s own position within the collage, as it is not an intended autobiography, but the display of a pursuit, filled with love and grief in equal measure. This first work also functions as a kind of codex, which weaves through and contextualizes the other works.

This is how to forget (2022) Top: “This is how to forget” Bottom, left to right: “Another picture was never made” and “All the party boys forgot about the party” dimensions Archival inkjet prints. Photo: Wren Gardiner

[Image description: Three grainy grayscale prints with bold, all capitalized text that is wavy and distorted that read “this is how to forget”, “another picture was never made”, and “all the party boys forgot about the party.”]

This is how to forget (2022) consists of three large text prints; one with a horizontal orientation that reads, “THIS IS HOW TO FORGET,” and a pair that are both vertical in orientation that read,“ANOTHER PICTURE WAS NEVER MADE” and “ALL THE PARTY BOYS FORGOT ABOUT THE PARTY.” These distorted, grayscale prints–featuring a sans serif text, all capitalized–feels like a message from another time. A shout from within the void. The patterned, black marks on the white paper expose them as xerox prints. If Trace 01 is a codex for Storey’s work, This is how to forget is the thesis for his art practice. Writing and images are inverse processes: an image allows us to create a narrative, while a text allows us to create our own image. Storey pairs these methodologies as a way of meditating on distance, desire, longing, and loss.

To name his practice with a word: hauntology. Hauntology, first mentioned by Jacques Derrida in his 1993 book Spectres of Marx, can be understood as “the idea that the present is haunted by the metaphorical “ghosts” of lost futures.” [2] This hauntological practice underlies the work of most of these Queer Pictures Generation artists. The collapsing of the past and present, for these artists, is directly in relation to the AIDS Crisis, which is the ghost that continues to loom over queer people and queer culture (we see this echoed, also, in the recurrence of queer TV shows and films set in AIDS-era America and the UK, making us relive this over and over again). Each of the phrases/poems/excerpts featured in these pieces are elegies, evoking a deeply ingrained sadness.

Pulsing (2022) From left to right: Motel/Tillmans and Charlie’s Denver, dimensions, UV prints on aluminum. Photos: Wren Gardiner

[Image description: Two images that feature overlapping text and pictures, both with intense blue. The one on the left shows two men kissing passionately with the info for the Columbine Motel on top, and the one on the right shows a disco ball cowboy boot with the name Charlie’s Denver overlaid.]

The last work I will examine is titled Pulsing (2022), and features two UV prints on aluminum: Motel/Tillmans, which is a double exposure of a postcard of a Wolfgang Tillmans photograph, and a motel business card from a western Colorado town which served as a liminal queer space for various peoples, activities, and connections; and Charlie’s Denver, a double exposure of Charlie’s, a gay country-western bar in Denver with a cowboy boot disco ball at its center. These two images are part of a larger body of double-exposure photographs of journals, ephemera, notes, postcards, pictures, snapshots, and receipts. We see here another permutation of Storey’s preoccupation with print media, queer histories, desires, and potentialities. The artist again allows the personal archive and the larger queer archive to bleed into and through each other. Through these double exposures, we see Storey’s approach of using photography as a mode of mark making, and the prints that he produces as a form of drawing/collage work. There are equal parts tenderness and nostalgia in these images, which contain all of the ideas that the artist expands upon in these more recent works: rural queerness, text, images of queer nightlife spaces, and personal documents like polaroids, journals, and ephemera. Storey uses various archives (including his own) as a way of exploring and reconfiguring/recontextualizing collective memories and desires.

A hauntological practice like Storey’s is fundamentally about a kind of rumination. This rumination takes form in the accumulation of images, texts, and ephemera that are imaged and re-imaged, worked and re-worked, circling the specter of the AIDS Crisis and the larger cultural impact that has had on queer people over the past four decades. There is tenderness, beauty, sadness, longing, desire, eroticism, and distance in Storey’s work. Each of these projects holds a punctum that is largely only legible by queer viewers. Punctum, as conceived by Roland Barthes in his 1980 book Camera Lucida, is the component of a photograph that wounds the viewer. The punctum is not an objective thing-- it can vary from person to person, or even not exist in certain images for some people, but Storey has honed in on a collective punctum, a collective wound for queer people, in both written and visual culture. While punctum traditionally only refers to images, I would assert that, because writing (and especially poetry) is an inverse of an image/photograph, the punctum would translate into language. There are lines of text that can pierce you much more profoundly than others. In short, Storey’s practice is a hauntological endeavor, which centers on a collective, cultural wound. It is important to note, however, that this is not a practice of despair - this is a healing process.

To touch queer archives is healing, restorative. It validates our contemporary existence and gives us both hope and desire for queer futures. Queer people often come from families that don’t reflect our queerness, so interpersonal queer relationships/kinships are in many instances lifesaving. This is why the loss of a large part of a queer generation is still so deeply felt. We lost much of our community (elders, lovers, mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, siblings). These archives have come to form a lifeline for many queer people, especially rural queer people who may not have an immediate community. This preoccupation with queer archives is twofold in our contemporary moment: reckoning with the impact of the AIDS Crisis, while also dealing with the attempts of American fascists to erase queer people from history and public life. Nathan Storey’s work is an intimate window into a larger cultural conversation between queer artists and histories: leaving his own trace.

Dillon Chapman— an artist, writer, and cultural critic— is HereIn’s Contributing Editor.

Notes:

“Pictures Generation,” Tate. Accessed February 16, 2023.

Ashford, James, “What Is Hauntology?” The Week UK, October 31, 2019.