Lorain Khalil Rihan with HereIn

[Image description: A black and white image of three people’s hands, with brown and olive skin, reaching toward a wall. On the wall hang many keys on hooks and a sheet of paper tacked up to the left. One person grasps a key, while another holds a pen, as if about to write their name on the paper.]

Art is rooted in the act of making. In intention. In establishing a connection between the viewer and the work to catalyze thought and emotion. If these qualities constitute art, then Returning to Palestine is, undeniably, art. A collaboration between artist Lorain Khalil Rihan and Dr. Jess Ghannam, Returning to Palestine is a web archive that presents an online trove of photographs depicting the Palestinian landscape and its people between 1948 and 1997. Yet the project offers far more than mere documentation—together, these images conjure the profound connection between a people and their land, the ties that bind amidst incomprehensible violence and provide hope for liberation.

I corresponded with Rihan about their process for the project, particularly within the context of the late-2023, early-2024 developments in the genocide against the Palestinian people by the state of Israel. As I work on editing this text, I keep coming back to something Rihan wrote on the Returning to Palestine website: “The act of remembering and dreaming is radical.” This is, I think, the most we can hope for from art—to help us remember a past that diverges from dominant narratives and dream of a better future.

—Elizabeth Rooklidge, Founder and Editor of HereIn

[Image description: On the left is a brown paper envelope from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees. On the right is a document for “Loan and Use of UNRWA Archive Still Photographs,” signed by Jess Ghannam.]

HereIn: Lorain, will you tell us how this project came about?

Lorain Rihan: My friend and co-organizer Dr. Jess Ghannam wrote to me in 2012 about a collection of black and white photographs that he had obtained from the United Nations Relief Works Agency in Gaza City in 2002. He asked if I would collaborate on an archival project that could maintain the historical foundation of the content and preserve the stories the images revealed. The collection included incredibly romantic scenes that depicted ordinary, everyday life in a Palestine that I was unfamiliar with. It also included the images of devastation that I grew up witnessing from a screen through satellite TV, and later through social media. I was overwhelmed by the contradictions in the photos and did not have the emotional capacity to hold this project with integrity.

[Image description: A woman with brown skin and dark hair wears an intricately embroidered headscarf. She sits on a rock wall, behind which stretches a landscape dotted with building and trees.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “Ramallah a city north of Jerusalem, West Bank.”]

In 2021, I wrote to Jess about revisiting the possibility of a collaboration with the photos. I had recently finished a seven year-long project, Where do we run when the earth shakes?, which memorialized the 1,415 Palestinians killed in Gaza in the 2008-2009 massacre, which was funded by the US and committed by the state of Israel. I immersed myself in a project that centered collective grief, and perhaps in some ways unintentionally reduced Gaza to a state of victimhood. At the beginning of the pandemic, I started a personal project of digitizing family photographs taken by my grandfather. I revisited the photos that Jess shared, and flipped back and forth between them and my family’s photographs that reflected the mundane. I was ready to shift my practice and to explore the contradictions that overwhelmed me nine years earlier.

As feared, the archive in Gaza City that Jess had visited and obtained the photographs from had been destroyed. He protected the physical documents for twenty years before our collaboration began. Each photograph from the collection has been digitized and physically preserved. Jess and I have been in conversation for nearly three years now about our role as guardians of the images and our responsibility in the production, consumption, and dissemination of media. We identified sixty-four of the photos from the 124 documents, and launched an online platform–Returning to Palestine.

[Image description: Sheep graze in a vast field. Palm trees line the horizon, while dramatic clouds fill the sky.]

[Image description: Text on a cream-colored background includes the description, “Sheep grazing in a field in the Gaza Strip, 1996.”]

HereIn: While I imagine that this collection of photographs would make for an incredible in-person exhibition, what are the advantages of having it live as an online project?

Rihan: Many of our conversations were about the deliberate destruction of Palestinian historical sites, especially places designated for knowledge production and information preservation as part of the Zionist colonial blueprint—to erase all traces of Palestinian existence. In Gaza, we are witnessing the eradication of Palestinians and the infrastructure of daily life. This includes the obliteration of historical libraries, archives, universities, museums, churches, and mosques. The Librarians and Archivists with Palestine recently released a report detailing several of the sites that have been damaged, destroyed, and looted, in addition to names of the information workers who have been murdered during the ongoing genocide by Israeli occupation forces. Their report contextualizes cultural genocidal practices as part of the Zionist strategy to erase Palestinian history, with examples from the 1948 Nakba, the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and during the Second Intifada.

Jess and I talked about experiencing anxiety around holding these documents, which could one day no longer physically exist anymore. Digitizing the images and making them available online felt like a responsibility on our end. An online platform also makes the photographs more accessible to generations of Palestinians globally who live in the diaspora/forced exile as a result of Zionist colonization. However, our hope is to also curate in-person exhibitions and programming.

[Image description: A group of men dance in a circle. They all have dark hair and brown and olive skin, and wear keffiyehs. One of them plays a flute-like instrument.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “Palestinian folk dance. Aida camp, Bethlehem, West Bank.”]

HereIn: On the website, you have the same photographs arranged in two ways: by time and by space. How do you think the images function differently within each framework?

Rihan: Initially, this was a technical approach because I was overwhelmed with the ephemeral qualities of the images and I needed a more tangible process to make sense of them. Organizing the photographs by time and space allowed me to map out the physical geography and the context surrounding the subject matter. But this approach also allowed us to explore how our relationship to time and space have been disrupted through Zionist colonization. We talked about the Palestinian Right of Return as a core principle for this project. Not just a physical return to the places named, but the restoration of relationships to a time and space that predates the Zionist colonization of Palestine.

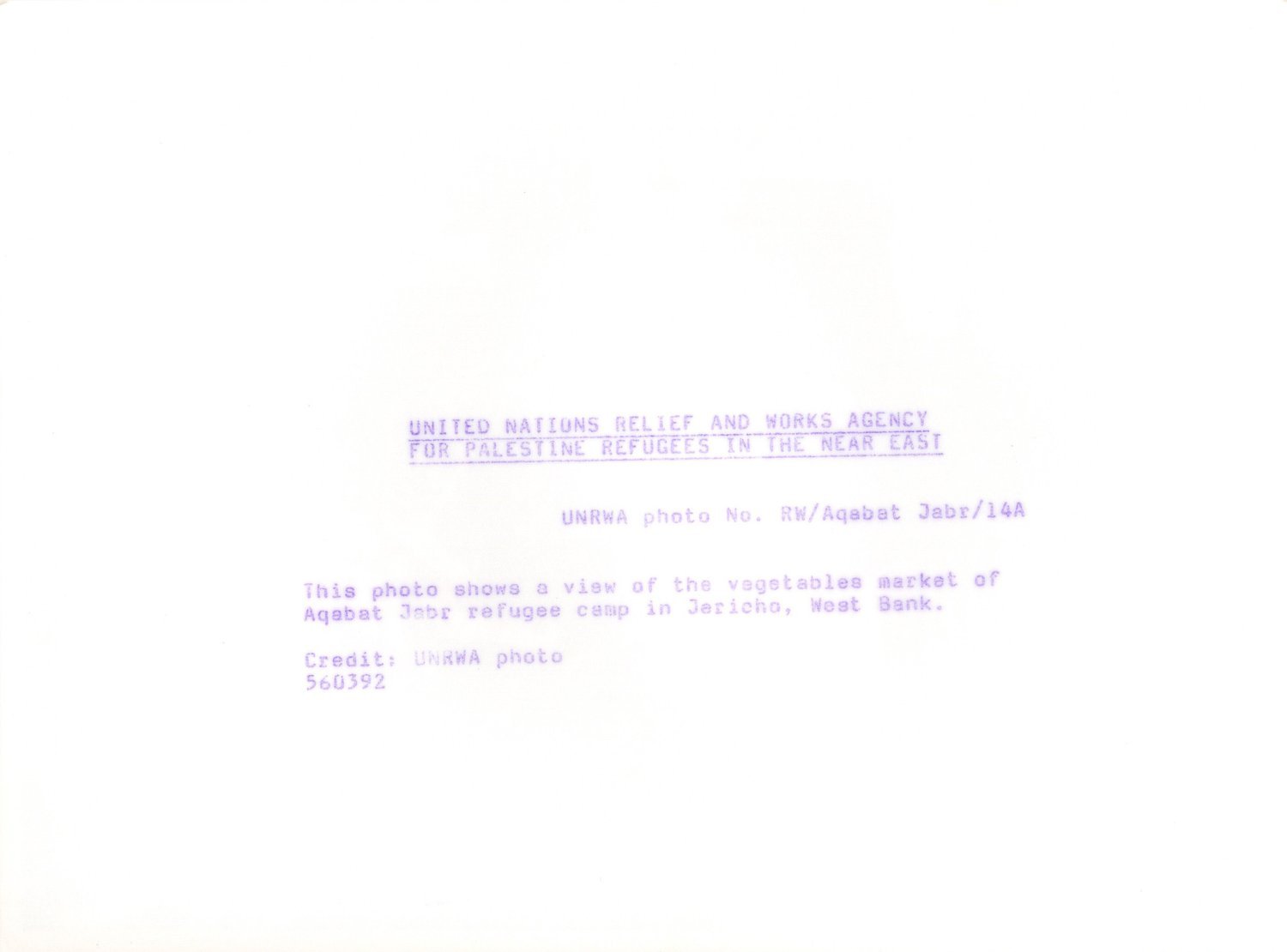

[Image description: A group of women and children, who have dark hair and brown and olive skin, shop in an outdoor market. On the right, a woman bends over a bin of vegetables, while on the left a child looks over her shoulder at the camera.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “This photo shows a view of the vegetable market of Aqabat Jabr refugee camp in Jericho, West Bank.”]

HereIn: You’ve made the careful decision to omit from this collection any images that depict explicit violence. This really strikes me, since we are, as you and I have been writing to each other since November 2023, witnessing a flood of violent images via social media during the ongoing genocide of Palestinians by the Israeli state. Can you tell me about why you and Jess made that decision for Returning to Palestine? How does this kind of non-violent imagery work alongside or intersect with the devastating documentation coming out of Gaza and the West Bank at this moment?

Rihan: We decided to omit the images from the collection that reflect Palestinian suffering and death out of our respect, commitment, and love for Palestinian life. Part of this respect for life is honoring the dignity of the dead, which doesn’t feel possible when our suffering is displayed. Flattening any community to a perpetual state of victimhood is dehumanizing. Normalizing the annihilation of Palestinian life is also an act of violence. Jess and I do not live in Palestine and we do not bear the brunt of Zionist colonial violence, so we are moving through the project with this consciousness to not make our community’s trauma available for consumption.

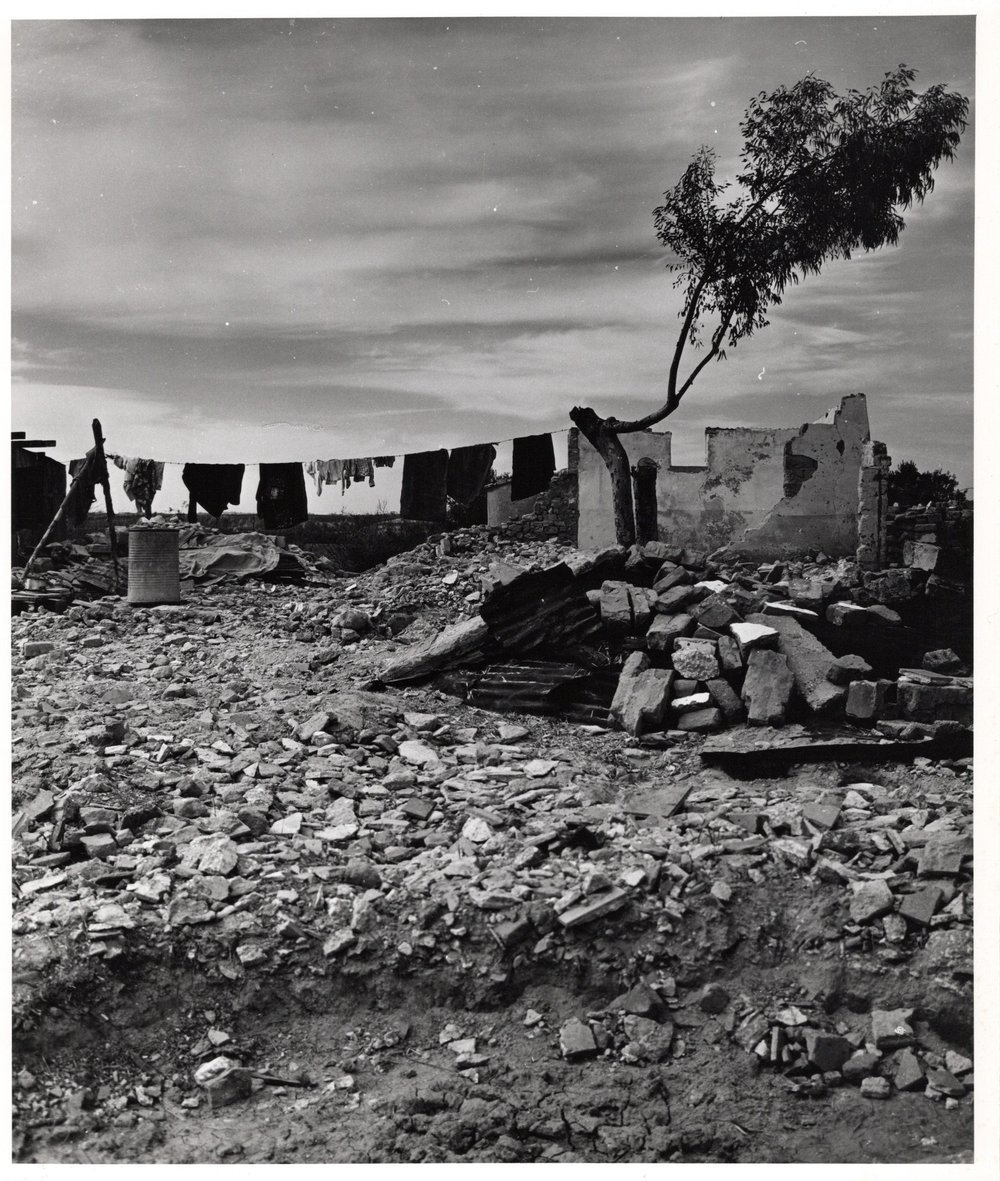

[Image description: A pile of rubble, with the remains of a dwelling on the right. A line hung with laundry stretches across the horizon, and a tree juts up into the sky on the right.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “Bureij Refugee Camp, Gaza Strip, 1961. A number of Arab homes in the Israeli-occupied Gaza Strip were demolished following the June 1967 hostilities. Because the families were homeless, UNRWA provided them with shelter. Agency rations were also issued on a temporary basis […] to those not previously registered with UNRWA, as an emergency measure.”]

The photographs from the collection that we chose to exclude from the Returning to Palestine platform serve as historical documentation that exposes the depravity of Zionist colonial violence. The imagery that Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank are sharing today through social media have a similar function—except that we are viewing it in real time rather than studying it as an historical event. Palestinians don’t want to create a spectacle of their dead loved ones by sharing photos and videos of slaughtered bodies. But they are sharing these videos and photos imploring the world to bear witness, to reject the normalization of their pain, to resist complacency, and to move into action to end a genocide that we are complicit in.

[Image description: Children, most of whom have dark hair and brown and olive skin, sit on a hill overlooking a landscape of fields, trees, and dwellings. Many of the children face the camera and look at each other with expressions of joy.]

[Image description: Very faint text on a white background includes the description, “Youngsters of Arroub Camp for Palestine Refugees […] near Hebron in the Israeli occupied West Bank.”]

In some ways the majority of the photographs presented on the Returning to Palestine page reflects a kind of parallel reality when comparing it to the imagery emerging from Palestine right now. Most of those images depict mundane street scenes, the tempo of everyday life, and breathtaking landscapes. Perhaps we would not be able to contextualize the exact time or place without the printed narrative on the back of the photos. But all of these photographs of Palestinian life were captured following the 1948 Nakba, when nearly 800,000 Palestinians were dispossessed of their ancestral homelands. I do think there is a convergence between the imagery coming out of Palestine today and the documentation from the Returning to Palestine collection. We can carry all of the stories, the joy, the grief, the dead and the living alongside one another, and all of this can act as visual blueprints as we journey towards a liberated Palestine.

HereIn: What are your hopes for this project moving forward? What are your hopes for the larger ways in which image-sharing and image-consumption function in the world?

Rihan: We want to work with Palestinian artists across disciplines in the motherland and in the diaspora/forced exile to activate the images and expand our imaginations around return. The ultimate dream for this project is for it to return and live in a liberated Palestine.

*Remarks from the artist: UNRWA has undergone massive efforts to archive historical documents created throughout the decades, and they have digitized over 10,000 prints. Many of the images shared here are recorded in UNRWA’s digital archive. The Returning to Palestine page specifically focuses on the media within our physical possession and we do not own these images or this content.

[Image description: A black and white image of three people’s hands, with brown and olive skin, reaching toward a wall. On the wall hang many keys on hooks and a sheet of paper tacked up to the left. One person grasps a key, while another holds a pen, as if about to write their name on the paper.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “The last of the tenst, Aida camp, Bethlehem, Jordan. After nine years of living in tents, since their exodus from Palestine, the 1050 refugees of Aida camp were summoned to the Distribution Center, where they go usually to collect their monthly rations, to be given something different—the keys to their new concrete block shelters. Although the rooms are small (average 9 x 10.5 ft.) and there are an average of 5 people to a room, the new units afford much better shelter from the violent winter storms of this region than the tents.”]

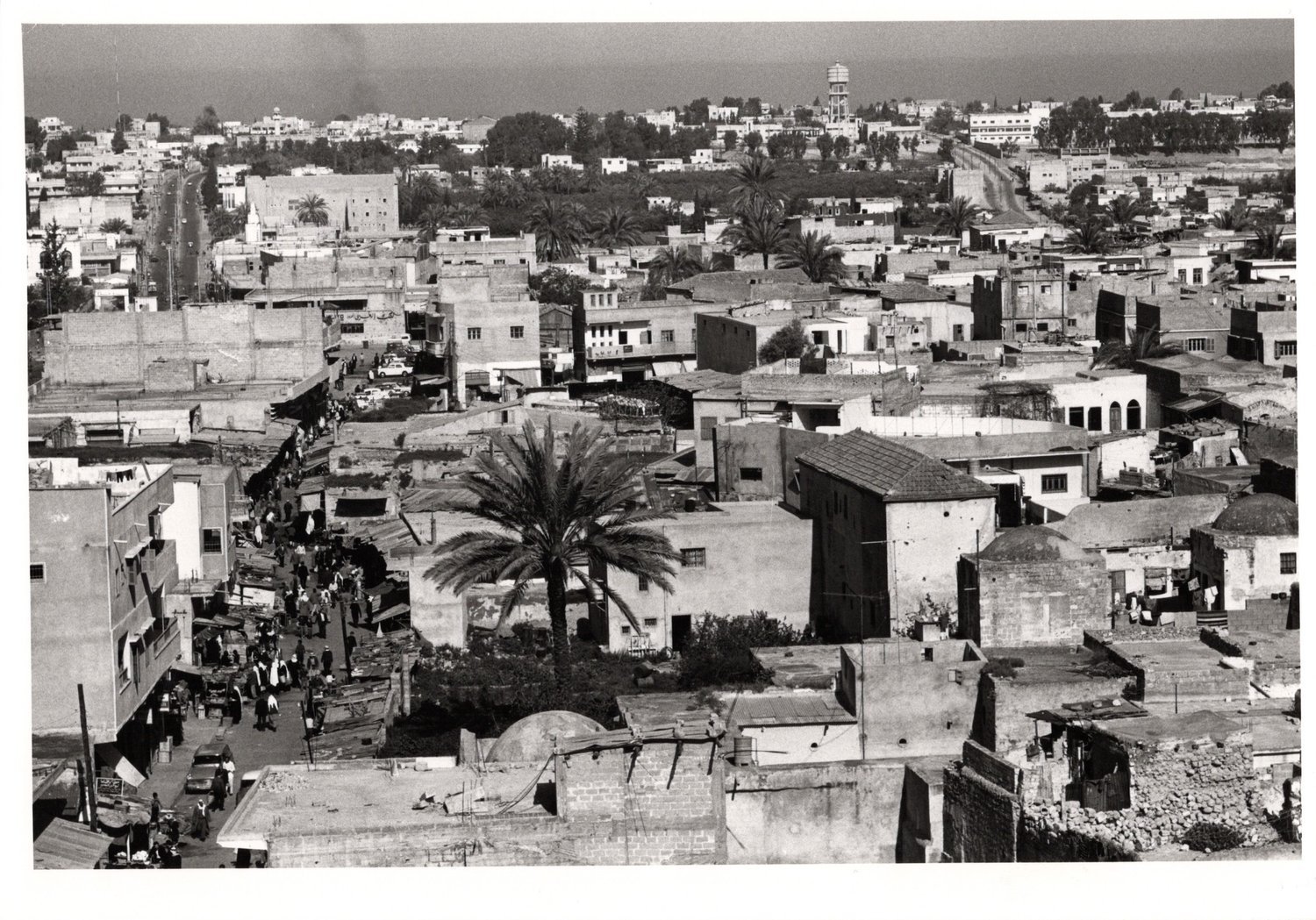

[Image description: A cityscape of stone buildings interspersed with palm trees. People walk down the road at the left of the images.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “Gaza Town on the Gaza Strip; 1971.”]

[Image description: Two men, who have brown and olive skin, sit at looms in a weaving workshop. Rugs are spread on the floor and are stacked, folded, on shelves against the back wall.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “Traditional Gaza rugs being woven in a workshop in Gaza Town.”]

[Image description: A portrait of a man, who has dark hair and brown skin, standing in the foreground with a hoe over his shoulder. In the background, a planted field stretches back to the horizon, which is lined with palm trees. The man’s brow is furrowed as he appears to look out across a far distance.]

[Image description: Handwritten text on a white background includes the description, “UNRWA photo, 1989.”]

[Image description: Dense groups of men, who have brown and olive skin, board fishing boats. In the foreground, a man is being pulled up onto the boat, while others reach their hands up for a lift.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “From the 1948 until 1967, Gaza Strip was administered by Egypt. The residents there were linked with the outside world by one narrow road through the 200 miles of Sinai desert to Cairo. Another exit was the Mediterranean Sea. This photo shows Palestinians leaving Gaza Strip on small fishing boats.”]

[Image description: Three people ride camels, trailed by a person on a cart, across a line of train tracks.]

[Image description: Text on a white background includes the description, “A scene from Khan Younis, Gaza Strip.”]

[Image description: A man, who has dark hair and brown skin, sits on a rock on top of a hill. He looks out over a landscape of fields and dwellings, all framed by trees on either side of the photograph.]

[Image description: Faint text on a white background includes the description, “Arroub refugee camp (population 6000) is one of 61 camps for Palestine refugees in Jordan. Syrian Arab Republic Lebanon end the Israeli occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. In 1949 the UN establishment UNRWA to provide welfare health and education services to the refugees. Today, 1/2 of the 2.5 million registered refugees live in camps, while the rest of the refugees live on their own in towns and villages of the Middle East.”]