Kirstyn Hom with HereIn

Passages, 2019, 9-hour durational performance and installation

[Image description: A Chinese-American woman sits at a sewing table in a gallery. She wears a red shirt and white apron, and appears in the middle of running a very long, white column of fabric through the sewing machine.]

In her meticulous work with textiles, Kirstyn Hom employs sewing to meditate on her family’s history as Chinese immigrants, against the backdrop of the recent rise in anti-Asian racism. She spoke with HereIn Editor Elizabeth Rooklidge about her background in fashion and how it led to a poignant and personal artistic practice.

HereIn: How did you get started making art?

Kirstyn Hom: I started making art at a very young age. I grew up in San Francisco and by the time I could hold a pencil, I was drawing. I participated in after-school art programs and then attended an arts magnet high school. So my background was very much like a traditional fine arts training, a technical and rigid way of approaching artmaking. I wanted to break free of that when I started my undergrad at UC Berkeley. The program there was very flexible and really opened my eyes to something beyond 2D, beyond the page. I loved my first sculpture class and did a lot of work with mixed-media materials. I ended up making a lot of wearable sculptures.

So fast forward, I thought I wanted to be a fashion designer. I spent a lot of time in the costume design department, helping design costumes for theater productions. I started taking evening classes at City College to really understand garment construction and pattern making, and I interned at fashion startup companies in the Bay Area.

Before I came to San Diego to start my MFA, I was working in the fashion industry— I was a designer and merchandiser for a company that sold to big department stores. So I got to understand all parts of the fashion cycle, which opened up my eyes to the nitty gritty of what I thought was very glamorous and creative. Like, this is what it means to mass-produce and make money with apparel. It was a breaking point for me in terms of seeing how labor worked. Even in that company, how labor was divided up by floor. The designers are on the first floor and they’re the most visible, they’re the ones making the decisions. And then the seamstresses and the cutters were on the very top of the floor of this building, the least visible.

It was kind of wild, because I was talking to my mom and she told me that my grandmother was a seamstress and she actually worked for the same big company. I would walk by these ladies working at the machines and I felt like I was seeing remnants of my own family history, the work that my grandmother did when she immigrated from China.

Video still from sau pin glow, 2021

[Image description: An elderly Chinese woman sits at a kitchen table, reading a document on a cream-colored piece of paper. She wears a purple and red floral-patterned top, and a Disney Snow White coffee mug sits on the table in front of her. The image has a blurred black frame around the edges.]

HereIn: Will you tell us more about your family history?

Hom: That was a big part of my work in the last year for my thesis, digging into that family history and really focusing on my grandmother. She passed away at the beginning of 2018, before I started the program. My grief was both for the loss of a loved one, but also losing connections to my culture. At the time, I was reading about David L. Eng and Shinhee Han's theory of “racial melancholia,” which is unresolved grief due to assimilation, immigration, and racialization. To know what you’ve lost, but not what is lost within yourself. It’s a feeling that lingers beyond mourning. I saw this as a form of intergenerational trauma that I wanted to process by understanding parts of my origin story that came before me.

What began as a few phone calls between my mom and I turned into a collaborative storytelling process with the entire family to fill in the gaps. Since my mom is the youngest of the family, she would ask my aunt, who grew up in China with my grandmother. They immigrated to the U.S. in the 1940s from a southern part of China, which is now Guangdong. My grandfather immigrated before they did, to find better opportunities and a new home. Their stories are a lot about navigating the instability of China at the time, having gone through the second Sino-Japanese war and the rise of Communism. What drew me closer to my grandmother’s immigration story was seeing how her experience shifted due to intersections of race, class, and gender. She took on the role of a single mother and was alone throughout the journey to the U.S. I hang on to certain memories, such as how she stitched small pockets in the lining of her jacket to hold her belongings as she left home. It’s these small details that have such presence in my imagination.

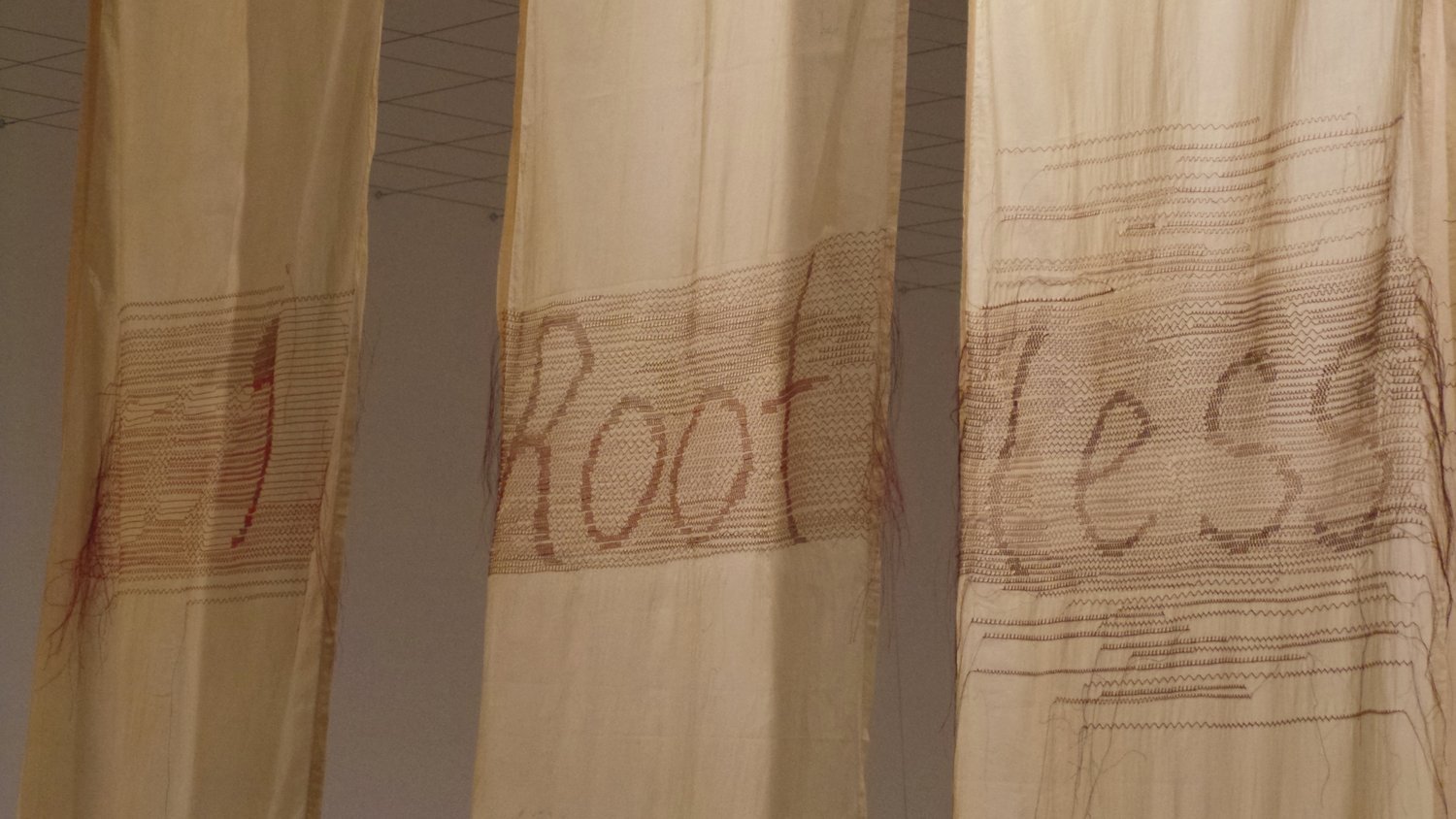

rootless yet, 2021, combed cotton voile, pomegranate dye, thread

[Image description: Seventeen tall, narrow fabric panels hang from the gallery ceiling in a line. There is red embroidery in the center of each yellow panel, with text faintly emerging on seven of the panels. Together, they read, “uprooted but flowering, rootless yet...”]

HereIn: This history appears in your thesis in a multivalent way. How did that project evolve?

Hom: I was initially thinking about my own processes and why am I so drawn to working with fibers and sewing, this kind of laborious, time-consuming, meticulous method. I wanted to look into my grandmother and the labor that she did, which was the only opportunity when she moved to Chinatown in San Francisco. I’d heard about my grandmother bringing piecework home and laying it out on the kitchen table. The family would push perfect points into the collar pieces with the ends of chopsticks. So work and home life were blended because of the conditions of being a first-generation immigrant.

A lot of my thesis was thinking about my relationship with her and the language barrier we shared. My grandmother never learned English. She lived here from 1948 up until 2018 but never picked up the language. My parents attempted to teach me, but I never learned Cantonese. There was this disconnect, these gaps in my Asian American identity, not being enough on either side. So I was thinking about the other ways my grandmother and I would connect, through different gestures of sharing certain foods together, facial expressions, and the pitch of our voices. This “in-between language” is something that I try to express in my work.

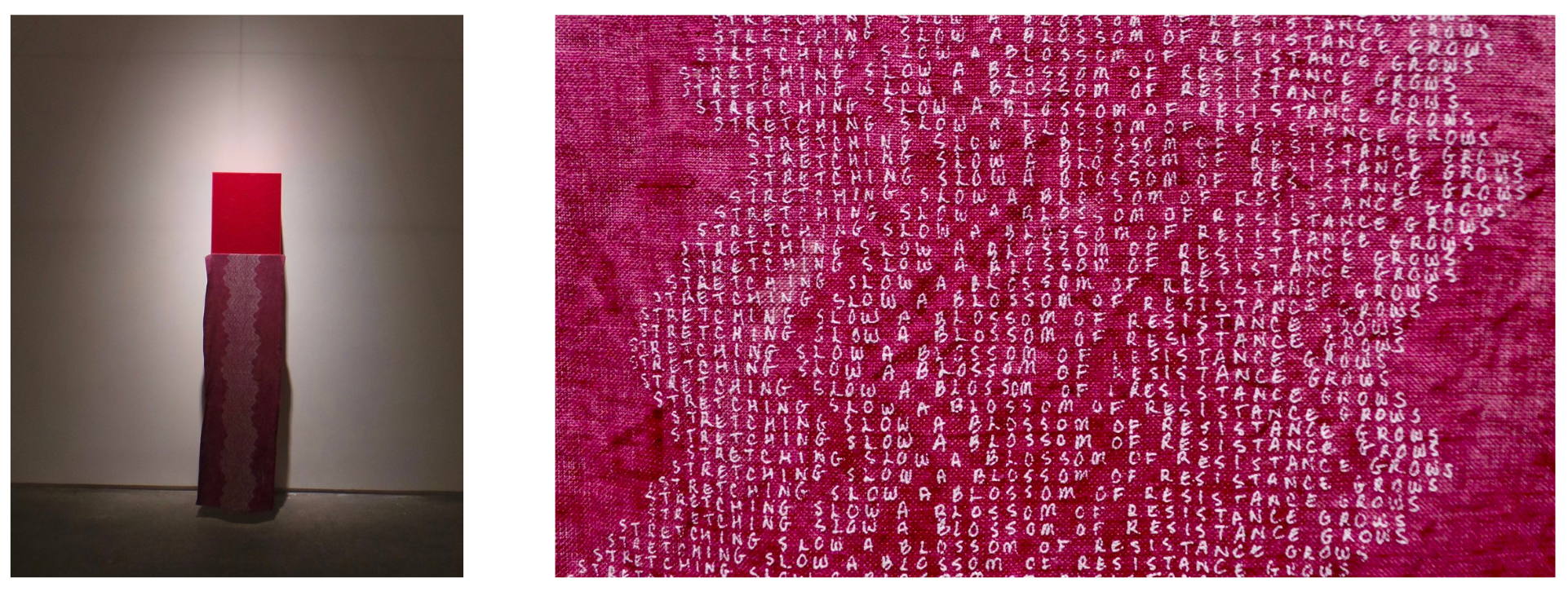

sau pin glow, 2021, lac, linen, home video, wax dressmaking paper, wooden box, 78 x 15 x 18 in.

[Image descriptions: Left: A wooden box covered in red dressmaking paper sits on a shelf at eye level, which is covered by a reddish-purple textile draped down to the floor. A vertical column of white embroidery extends the length of the fabric. Right: A closeup of the fabric. The embroidery reads, “Stretching slow a blossom of resistance grows,” repeated from top to bottom.]

HereIn: It does seem evident that the physical act of making in your work carries a lot of meaning. Can you tell us more about the relationship between a gesture that’s physical and repetitive, and conceptual and emotional meaning?

Hom: I see the labor that I do through the sewing machine as a form of translation. I search for new languages that can emerge through textiles. A strand of thread from a spool wraps into a stitch, those stitches can build into a line, and eventually a fragment of a text emerges. This process of sewing back and forth is similar to writing on a piece of paper. As I’m doing this long durational sewing, I respond to the time, repetition, and anonymity that was required in my grandmother’s factory piecework. So for me, I’m interested in turning something that comes out of the machine, that is so mechanized and precise, into a reflection of my touch. I look at the slight curves, knots, and loose threads as this raw stream of thoughts running onto the page.

I Sau (绣) Her Name, 2020, linen, thread, wood shelf, 8 1/2 x 2 x 1 ft.

[Image description: A long, narrow textile hangs on a white gallery wall. The scroll-like length of fabric bears dense, horizontal lines of red embroidery, with Chinese characters appearing from top to bottom.]

HereIn: That brings me to the idea that, I think, in Western art history and in our culture in this country, we generally associate sewing and embroidery with domestic, almost personal work. It’s really interesting to me that you’re drawing out how, with this sort of work on a commercial scale, a human is functioning like a cog in the wheel of mechanized labor. That’s often invisible to many of us. I wonder about this tension between domestic labor— work in a personal space— and this sort of capitalist production.

Hom: Right. My grandmother was very much attached to the whole production and when she finished parts of the garment, which are essentially handmade— it went through her hands— it would then be hanging in a department store. My mom has a really good story of finding a garment my grandmother made in a store— she looked at the tag and it had my grandmother’s employee ID on it. Once that garment is hanging in the store, it’s stripped of her identity. By working with craft, I’m pushed to interrogate the gendered expectations tied to these methods; parameters for practical use, function, or obedience to domestic space.

In an installation and performance piece, Passages, I emphasized this tension between the sewing machine and the self through sound. I collaborated with a music PhD student, Kevin Schwenkler, to use a contact microphone to amplify the body of the machine working. The noises were reminiscent of horses galloping, a heavy wheezing, a train on the tracks. In the background, there is audio of my mother and I telling parts of the department store story, and Schwenkler programmed a sensor in the microphone to pause the dialogue once the machine started sewing. So, as I was sewing this long apron, viewers were able to hear the machine fragmenting this stream of memories.

I Sau (绣) Her Name (detail), 2020, linen, thread, wood shelf, 8 1/2 x 2 x 1 ft.

[Image description: A closeup of red patterned lines on white fabric. Loose threads hang from the fabric’s edges.]

There was one point when I was writing a lot of poetry to process the pandemic and witnessing the rise of anti-Asian sentiment. I was seeing how a lot of elderly and first-generation immigrants were being targeted. I couldn’t help but reflect on my identity as a grandchild of immigrants and reckon with the meaning of being Asian-American at this moment. I wondered, how will the story continue?

Some of the textiles that I was making had pieces of that poetry stitched into different panels, the text fragmented, in a way. My idea for that particular piece— Rootless Yet, which is made up of hanging, yellow textiles— was a way to position the viewer in an in-between space. They’re walking through the pieces of the words, kind of physically weaving them together. Putting the phrase together.

rootless yet (detail), 2021, combed cotton voile, pomegranate dye, thread

[Image description: A closeup of three of the fabric panels. Amidst embroidered, horizontal red lines, text reads, “Rootless.” Loose threads hang down from many of the embroidered lines and letters.]

The fabric was dyed with pomegranate skins. I was reading a lot of Asian American literature and poetry at the time, including a book by Frances Chung called Crazy Melon and Chinese Apple. She’s talking a lot about her identity and her experiences growing up in New York City’s Chinatown. I was really inspired by how she illustrated that relationship through the everyday objects she had in her home. Because of trade around the Silk Road, Europeans referred to the pomegranate as the Chinese apple. I was interested in the transcultural attachment to these objects— due to these interactions, that identity or label is never stable.

The pomegranate skins dye the fabric not in a red hue, but this bright, golden yellow. Using that dye, I had to confront my own relationship to the color yellow, which was so racialized when I was growing up in the nineties. Like, I was always picked as the yellow Power Ranger. I didn’t want to be given yellow objects because the color appeared rotten and sickly to me. And so for me, this was a way to reorientate myself in relation to that color, creating space for myself and others during a time of a lot of violence and fear. How can yellow be something more: something joyful, warm, and expansive?

Overall, my practice seeks to work with loss to find moments of possibility. Although my recent work is informed by family history, the focus is not simply retelling the past. Instead, I want to use these memories as a way to create new spaces of belonging. Within these modes of suturing and mending, I like to leave things unfinished in some way, a hint that the stitch continues. These gaps and inconsistencies bring me into this fluid state, so I can find points of departure

This interview has been edited by HereIn and the artist for length and clarity.