Alida Cervantes with HereIn

Installation view of Alida Cervantes: La Nueva Pastelera, Galería Internacional CEART Tijuana, 2022

[Image description: Eight portraits arranged in two rows. The paintings feature light-skinned men in colonial dress, with powdered wigs, sashes, and other embellishments. Several paintings have images of nude female torsos painted on top of them. There are three paintings hanging in the top row and five on the bottom, where they are stacked on cinderblocks or leaning against the wall.]

Alida Cervantes's paintings find a balance between visceral lusciousness and grit. That they are raw and immediate while also deeply steeped in history reflects the timelessness of their subject matter: the construction of socio-political, cultural, and racial hierarchies and their insidious influence. Cervantes's work draws specifically on 18th-century casta paintings ("casta" is Spanish for "caste"), a genre of painting in colonial Mexico that illustrated the racial makeup of what was then "New Spain." The paintings were racist mappings of the intermixing between Amerindians, Spaniards, and Africans, based on the deeply prejudiced belief that increased intermixing led to less racial "purity." Casta paintings enforced a hierarchical system of classification in which race was directly tied to socioeconomic status. [1] Cervantes often references visual tropes from these paintings to highlight their continued relevance.

She speaks with HereIn’s Contributing Editor Jordan Karney Chaim broadly about her development as a painter, the performativity of her process, and a consciousness uniquely shaped by life on the border.

HereIn: I want to ask about your experience as a binational artist in the San Diego/Tijuana region. There are a lot of artists that have built careers here, or who move back and forth, but you literally grew up on both sides of the border.

Alida Cervantes: When somebody refers to me as a border artist, I’m like, what does that mean exactly? That I’m on the border? That I’m making art about the border? My work isn’t directly about the border, but my experience as a trans-border person totally influences my work and my process. Of course I also know that there are people who are not from the border, they haven’t experienced a life of crossing the border all the time, but they make work or exhibit here and then suddenly they are a border artist.

QUE HUBIERA SIDO DE MI SI TU ESTUVIERAS AQUI, 2017, oil on wood and found spray-painted wood, 96 x 96 in.

[Image description: A loosely painted image of two elegantly dressed women, one with very black skin and one with white skin, walking through a wooded landscape. The painting is propped up on a wooden box and set against two wood panels covered with graffiti.]

HereIn: These ideas that you’ve been exploring— racial and class divisions, social or cultural hierarchies and how these constructs change from the Mexican context to the U.S. context—are issues you’ve been confronting your whole life while moving through these two parallel but obviously distinct realities.

Cervantes: For me I think the border is more of a psychological state. That psychology develops in somebody like me, who lives like this, and then that affects the work. It’s a different approach than addressing illegal immigration, or national borders, etc. In my case, crossing the border the way that I do, I can imagine it must create a different kind of brain.

In other border regions, by comparison, you might be crossing into different realities, but the realities could be similar. Somebody crossing every day between Italy and Switzerland, or maybe France, is crossing into a different reality as far as language or food, but the differences between Tijuana and San Diego are just so huge on so many levels. And that affects the way that you see yourself in relation to others. It affects the way that you’re treated. It’s very deep and has so many layers. From the time I was a little girl I’ve been questioning these things and analyzing what was happening to me. And all of that comes into the work.

Another thing that’s really interesting to me is that everyone is aware of the border with San Diego, but nobody really talks about the border that exists between Tijuana and the rest of Mexico, too.

SENSENSIBILIDAD, 2013, oil on wood, 6 x 7 ft.

[Image description: A painting of a nude light-skinned woman and a man in colonial dress seated on an ornate red sofa. They are set against a gray background and a black and white checkered floor. A gray cat sits between the woman's splayed legs and the man reaches down towards it.]

HereIn: You mean the perception of border communities versus the interior of Mexico?

Cervantes: Yeah, I mean, the interior of Mexico is like, the center of the empire, and we’re seen [in Tijuana] as this peripheral society that is closer to the United States than to Mexico. We’re seen as having a different kind of “Mexicanness.” It’s really interesting on many levels. My father came from Mexico City, so I experienced that perception of the border even in my home growing up. My father was constantly making that comparison like, here it’s this way and in Mexico it’s that way—just this constant idea that the superior thing exists outside of where you are.

HereIn: You grew up in Tijuana, went to school in San Diego, then in Tijuana, and then started to paint when you travelled to Florence at 19. I see that you didn’t decide to get your MFA until you were 35, so what was your artistic practice like in your 20s? What made you decide to pursue an MFA?

Cervantes: Growing up, I hated school. I did my undergrad at UCSD, but I really just wanted to be in Italy because that’s where I was painting. So when I graduated from UCSD, I went back to Italy and I was happy to be able to just concentrate on painting. I got tired of Florence, and wanted to go to a big city. So I went to New York City and lived there until shortly after 9/11. While I was there I was basically just surviving. I never showed. I came back to Tijuana and set up my studio. I was showing here and there, and the Museum of Contemporary Art was interested in Tijuana artists—this was during the time when inSITE was really big—and so the museum got to know me, and I was included in Strange New World: Art and Design from Tijuana (2006). I started teaching at the La Jolla Atheneum, and I got a show there, I showed in LA. At some point, my friend Yvonne Venegas, who was doing her Master’s, talked me into doing one as well.

EL RECHAZO DEL NEGRO, 2012, oil on wood, 5 x 7 ft.

[Image description: A nude pale-skinned woman stands in a loosely painted landscape with trees. A dark-skinned man in colonial dress stands with his back towards her and looks back over his shoulder. A light-skinned man's head watches the scene from behind.]

HereIn: You talked elsewhere about this moment in grad school when one of your teachers looked at your work and asked, “are you making images, or are you making paintings?” I’m interested in this moment of transition—when you reoriented your practice from replicating other images to the brand of expressionism that you’ve developed.

Cervantes: When I started to paint, I really wanted my paintings to look like what I was painting. If I was painting a person, I wanted it to look exactly like that person. It didn’t have to be photorealist—I wasn’t interested in rigidity in terms of brushstroke, I didn’t mind if it was a little bit loose, but I wanted it to look like the thing. And that was my motivation for painting. If I was getting the painting to look like the thing I was painting, I was being successful, therefore felt good about it.

At first, I was painting from real life, then from existing photographs, and later my own photographs. When I was in grad school I started to paint from collages. I would create these digital collages, print them out, and paint them. I eventually got to a point where I felt like a slave to the images. I was working so hard to replicate them, but I felt there were no visible traces of me in them. I had no agency. And so I took a 180-degree turn.

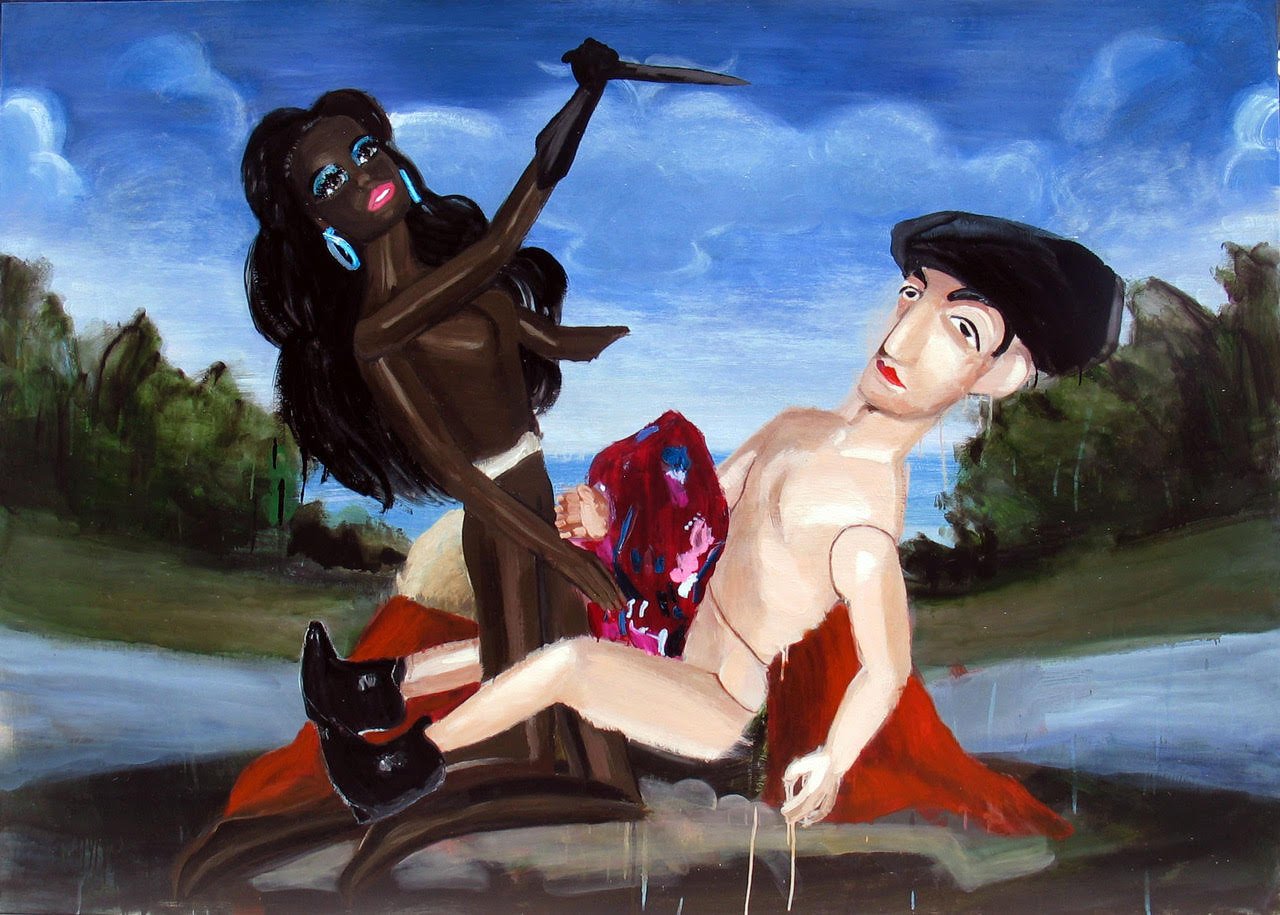

MATADORA, 2012, oil on wood, 5 x 7 ft.

[Image description: A very dark-skinned woman with the face of a Barbie doll raises a knife over the body of a pale-skinned man. He is nude except for black boots and a black matador's hat. He holds a red cape. They are set against a wooded landscape with a stream and blue skies.]

I remember at my graduate thesis show—which was completely different than anything else I’d done—my professor, Rubén Ortiz-Torres, said something to me and I didn’t really understand what he meant. He said, “Alida, you did what you wanted to do.” At first I thought, “well why wouldn’t I do what I wanted to do?” and then I understood. There’s a lot of pressure as an artist—supposedly we should follow our interests, but there can be a lot of pressure to produce certain things and in a certain way. The art world expects certain things, especially if you’re going to work with certain galleries. I needed to discover myself and my process, possibly at the cost of not having more success as an artist. That’s when I started to think more about my paint application, what kind of images I want to use. It’s an ongoing process.

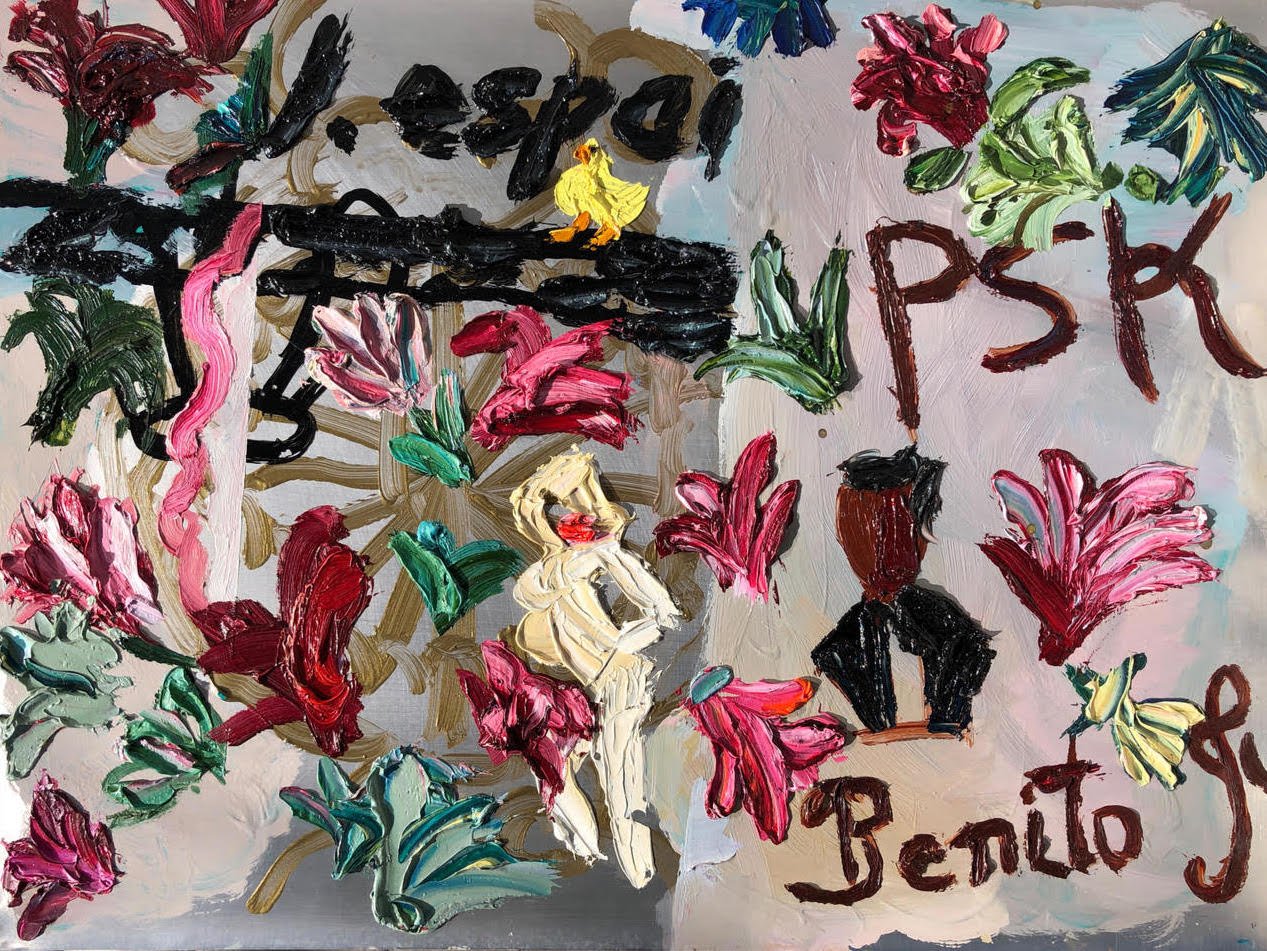

Untitled (from La Reina Quiere Coco), 2019, oil on aluminum, 12 x 16 in.

[Image description: A background of gray-mauve is covered in heavily textured flowers and leaves in a range of reds, greens, and turquoise. There is a gold armature behind them and several letters and word fragments scattered throughout. The word "Benito" is visible at the bottom right.]

You know how certain machines, certain gadgets, have settings on them? That’s how I feel when I’m painting. I feel like I have all these different settings that I can paint with. I feel like a lot of other painters work in only one setting, and that’s how the art world comes to know their style. I’ve always struggled with the fact that I have these 20 million settings, and I think that part of the reason I have all these settings is because I live on a border. I don’t have just one reality; I am navigating all these different realities at one time. So when I paint, it’s a struggle because there are so many different ways I can imagine making a painting: how am I applying the paint? What am I feeling? Do I want to be aggressive? Do I want to be submissive? It’s like sex—every time you have sex it’s different. It’s kind of a struggle sometimes, but at the same time it keeps me really interested in my own work.

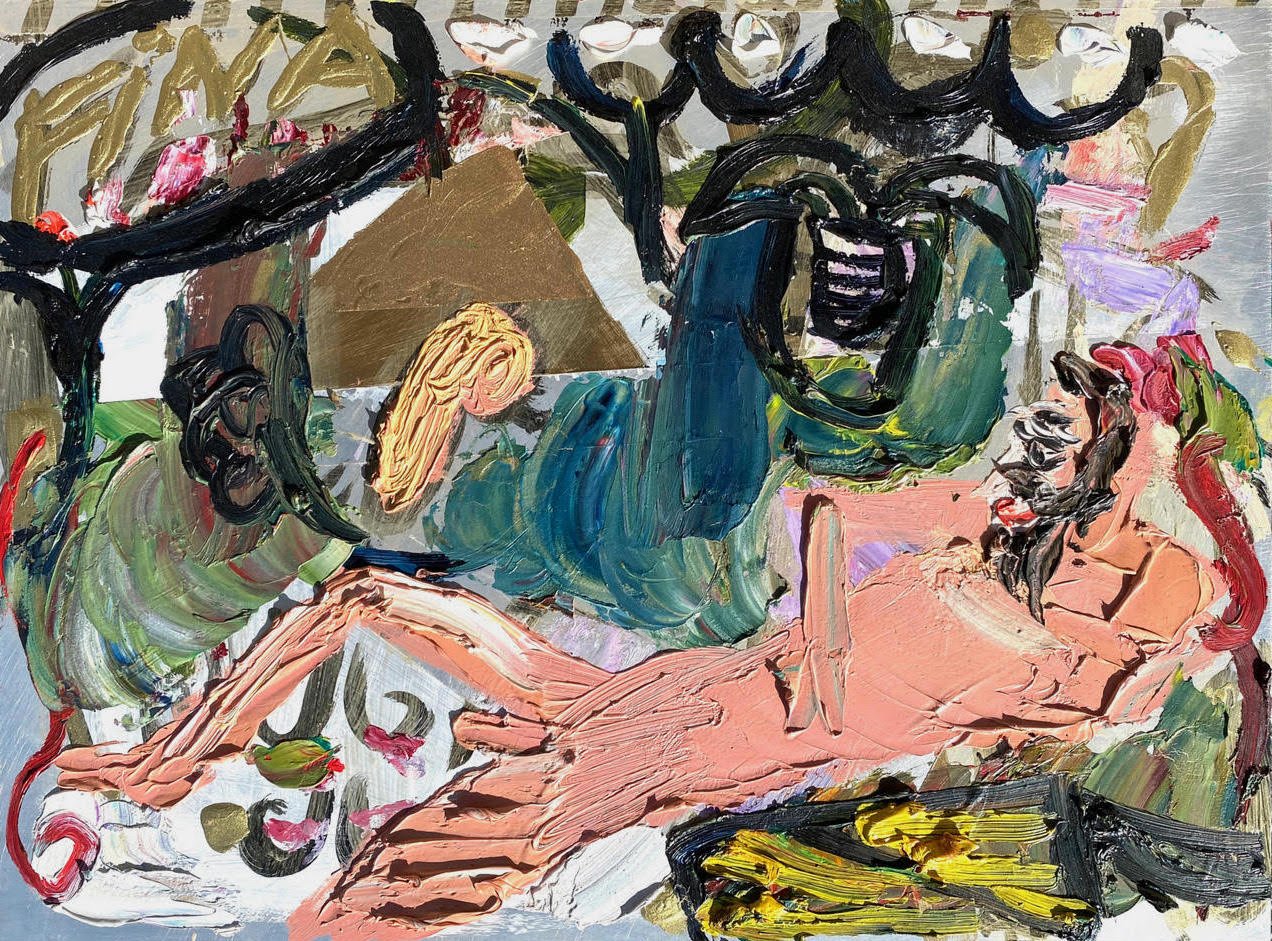

Untitled (from La Reina Quiere Coco), 2019, oil on aluminum, 12 x 16 in.

[Image description: A heavily painted abstract image depicting a nude pink-skinned male figure lying across the bottom right. Colorful swirls of mixed paint in blues and greens surround a sandy-colored pyramid shape. Heavy black lines are layered on top, and the word "fina" appears in gold at the upper left.]

HereIn: Can we talk a bit more about some of your recent work? Is there a particular storyline you were tracing in La Reina Quiere Coco? Are there any specific characters?

Cervantes: To me, those works are all still casta paintings, but just more uninhibited. They’re based on loose drawings I was making in my sketchbook at night before I went to bed. I kept imagining interactions between a couple—the couple is always interracial, or inter-class, they come from different places, but they’re together and there’s always some drama going on between them.

HereIn: I love how much drama there is in your work, as well as the performative aspects of your practice. You’ve talked about the paintings as being operatic, and you’ve also described your process as a kind of male drag. I’m so interested in how this drag persona emerged. I also think it’s really interesting that, with this drag character, you kind of embrace the oppressor/aggressor role in your critique of these power dynamics.

Cervantes: About ten years ago I created my drag character—El Puro, a Cuban Timba musician. Timba is basically salsa on steroids. It’s very hypersexualized and virtually all the performers are men. To me, painting is exactly like sex. Some people want to get to know somebody very profoundly first; others just want to have sex. And when they have sex with that person, does it have to be penetrative? Do they want to have foreplay? All of those things transfer into the painting process. For maybe the past four years or so I’ve identified as a man when I’m painting. I saw myself as a man and my paintings as women, as conquests or potential conquests. I would think about how much time to devote to them. Do I just want to give myself pleasure? Do I want to discover them? Do I want it to be fast? Do I want it to be slow? I don’t really understand why I identified as male, because I could have very easily identified as a woman. Must be something to do with my oppression as a woman. For me painting does become a performance. It becomes a power relation in and of itself. But I actually haven’t seen myself like this in maybe the last eight months. I hadn’t even noticed it myself, but now that were talking about it, in my last series of paintings I haven’t been thinking like that at all. I don’t think I’m there anymore. I think I’m at a point where I’m feeling less polarized and so am listening more.

Untitled (from La Reina Quiere Coco), 2019, oil on aluminum, 12 x 16 in.

[Image description: A colorful surface covered in thick paint ranging from yellows, blues, and greens, to pinks and shades of lavender. A light pink abstract female form sits at the center of the images, next to a gold table. A peach-colored bird is perched above her head.]

HereIn: How interesting. So how are you thinking about it now? Are you thinking of yourself as yourself? Or are you someone else?

Cervantes: I think I’m just myself now. And let me add, the male identification wasn’t always present. It developed over the last several years, as I was painting more expressively. I think maybe what’s happening now is that I’m finding a middle ground between the rigidity of my earlier work and expressiveness of my recent work. Because I’ve become more comfortable pushing past my own limitations. For example, when I was making more representational paintings, I was constantly worried about “ruining” them. Either I was making it look more like the thing or less like the thing, and in my mind, and probably in the mind of a lot of painters, the question became, “am I ruining it?” That produces a lot of rigidity, and I’ve kind of broken with that. I’m not going to torture myself with that question. I’m actually going to ruin it on purpose. “Ruining” the painting and then recovering some of it is kind of my process now.

Notes

For more on casta paintings, see Casey Lesser, "These 18th-Century Paintings of Interracial Mexican Families are Based on a Lie," Artsy, June 27, 2018.

This conversation has been edited by HereIn and the artist for length and clarity.