Chantel Paul on Farrah Karapetian

Yes You Can (Blind Faith), 2020, unique chromogenic photograph, 24 x 64 in., courtesy of the artist and Diane Rosenstein Gallery

[Image description: A wash of deep purple, with splatters and drips at its edges, spreads along the left side and bottom of the image, while a span of translucent yellow occupies the top center and right. Where the purple and yellow meet is the dark silhouette of a city skyline. Yellow script across the image reads, “I can’t find my way home.”]

While often considered a photographer working in large-scale, Farrah Karapetian is not shy about dancing beside this medium and meandering into other realms of artmaking— such as sculpture, performance, or drawing—as part of her practice. In fact, she is fueled by a profound sense of openness and curiosity, coupled with an intent desire to disrupt, provoke, and communicate: a thread that runs through the work Karapetian has made over the past decade. Her finished objects are a refreshing beacon, coming at a time when photography has reentered a space of unfettered experimentation.

Got to the Mystic, 2014, unique chromogenic photogram, 97 x 82 in.

[Image description: The silhouette of a drum kit spread across two vertical, rectangular images. The silhouette is bright white against a variegated orange background. The figure of a person is partially obscured behind the drums on the far right.]

I first saw Farrah Karapetian’s work in person at her solo exhibition Stagecraft (2014-15) at Von Lintel Gallery in Los Angeles. I had seen the series reproduced online, but walking into the exhibition was something different entirely. I was confronted and captivated by the combination of 1:1 scale of the subject of each work, as well as its boldness of color. The cyans and greens, oranges, reds, and yellows transformed the gallery into a reverberating space of mood and chord. Pun intended, as this body of work recorded instruments and beats played by her father, capturing him at the drums and “transcribing his marks on drum skins.”

In the Wake of Time, In the Break of Time, 2015, glass and steel, dimensions variable

[Image description: A drum kit stands in the corner of a room with white walls and a gray floor. The drumheads and cymbals are clear, and one of the cymbals is a transparent red. The drum kit’s shadow falls on the wall behind it.]

Presented in her choice of unique, oversized color photograms, the two-dimensional objects were accompanied by an exquisitely lit sculptural replica of her father’s drum kit that was immortalized as subject in many of the images in Stagecraft. Capturing these drums and other instruments as abstracted and double-exposed negative forms, Karapetian masterfully wove together color and emotion throughout Stagecraft, using specific lighting and the gallery itself as a backdrop. Every bit of the exhibition was in harmony with the space.

Describing herself as a site-responsive artist, Karapetian integrates her artworks into each space as an interconnected entity. Peeling back the layers of Karapetian’s work is fascinating and fundamental to understanding her prolific output. While working primarily as a visual artist, she is equally devoted to language and fully aware of the power of the written word, drawing inspiration from writers and artists alike.

When speaking with Karapetian about her process and work, the artist’s intensity is infectious. Photography becomes a way of communicating and reasoning, of making sense. There are few boundaries for her use of the medium and how it informs the sculptural objects that accompany the photographs in her installations. Karapetian has moved photography from an instrument of documentation to one that creates visuals based on questions about personal relationships and social/cultural queries. It’s a process bordering on ritual, starting with a question that leads to experimentation, which produces a possible answer as a doorway to subsequent ideas. Karapetian flows with it all, embracing chance as much as she maintains a command of her materials through a deep understanding of the photographic process that allows for both experimentation and control.

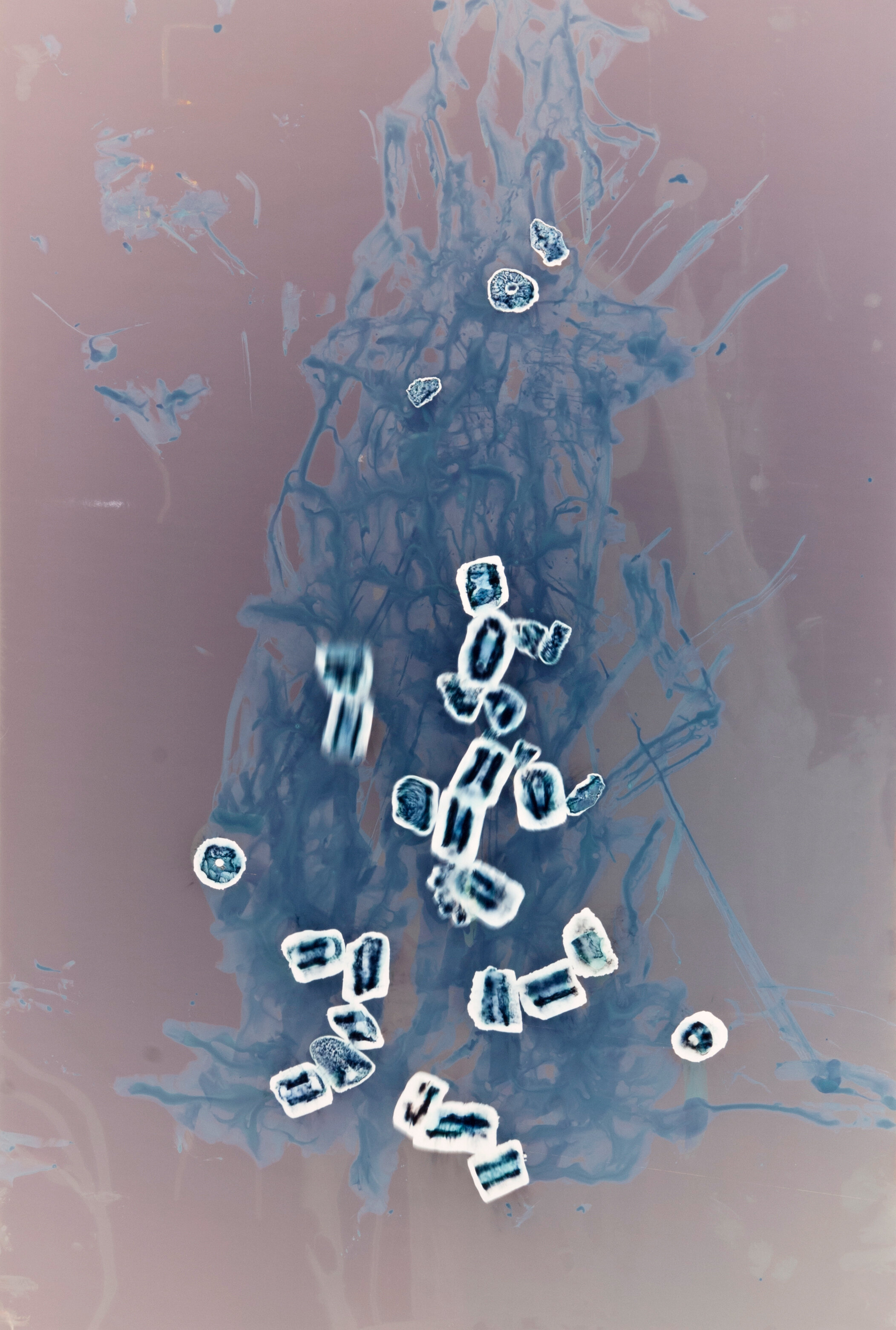

Slip 43, 2013, unique chromogenic photogram, 30 x 20 in.

[Image description: A mass of soft blue lines, both sketchy and fluid, are centered on the image’s mauve background. Small crystalline forms— rectangles with rounded edges and uneven circles, blue and edged with bright white— are scattered across the lines.]

In her 2013-14 series Slips & Pushes, the artist tried something new: using ice on chromogenic paper in the darkroom. She started with smaller cubes, capturing their form directly on the paper’s surface. These cubes were slippery and fickle, which led to the realization that a larger, flat block would make for a better result and could be controlled or pushed. As a subject, the ice is as translucent in these images as it is in reality, a feature that the photogram process uniquely captures. While this began as a study for an installation at the Orange County Museum of Art, the work shifted into something more expansive, paving the way for a series that investigated much more nuanced ideas of identity, agency, and a personal history that Karapetian has continued to investigate.

Lifesaver, 2015, unique chromogenic photogram, 56 ¼ x 40 in.

[Image description: The white silhouette of a circular life preserver against a green, yellow, and brown background. Below the life preserver are forms suggesting bubbles in water.]

In 2015, Karapetian embarked on a creative journey inspired by the mass global migrations taking place throughout the world. Her attention was particularly drawn to individuals in Havana making plans to leave Cuba to travel to Florida by boat. She juxtaposed this subject with research on her own family’s immigration to the United States, beginning to unravel this history as someone of Armenian, Italian, Russian-Jewish, and Irish heritage. Relief (2015-16) was the result of combining these two narratives. Using objects such as ice, metal, water, and a series of safety devices such as life vests and ring buoys, Karapetian’s darkroom performances deftly recreated the feeling of swimming and traversing the ocean.

Carefully chosen colored filters in combination with Karapetian’s physical movements— such as placing the objects onto the paper under the light of the enlarger—created visuals as thick and encompassing as an uncertain journey by sea might feel. The photographs were accompanied by an installation of an orange life vest cast in ice melting on sand and a video of the same flotation device melting into the sea over the course of 16:20 minutes. Ranging from complete abstraction and metaphor to recognizable imagery, the artist constructed an active visual narrative that was as haunting and as it was luscious.

Cinderblock negatives, 2017, rebar, resin, and paint, dimensions variable

[Image description: A gallery with white walls and a gray floor. On the right is a sculpture composed of rectangular cuboids made of rebar, many stacked on top of each other. While the sides of most of the structures are open, seven have a sky blue-colored panel, which faces the viewer. The sculpture’s shadow is cast on the wall behind it. On the left wall hang two vertical works of art, which feature the silhouettes of structures in the sculpture.]

Throughout her life, Farrah Karapetian has had a close relationship with her family, which cultivated a deep desire to travel and immerse herself in cultures outside of the United States. In 2016, she mined her relatives’ multi-cultural migration history further, expanding on what she had begun with Relief. Traveling to Europe and Russia as part of a residency with CEC ArtsLink and funded in part by a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Fellowship, Karapetian traced the routes her grandparents traveled during their emigrations. She spent time in each of the villages where her grandparents grew up: in Armenia and Italy on her father’s side, and Ireland and what is now Ukraine on her mother’s side.

The resulting work of Building Dwelling Thinking, shown in 2017, was the culmination of her travels and the experience of her stateside return amidst Brexit and the U.S. election of 2016. For this series, Karapetian constructed hollow cuboid structures out of rebar, creating large, crude sculptures. These functioned on their own as objects and also became the layered subjects of large-scale photograms. Stark white backgrounds and voids are punctuated by rich yellows, purples, cyans, and rusty red oranges, sometimes maintaining the jagged-edge reference point of the rebar.

Change, 2017, unique chromogenic photogram, 40 x 49 ½ in.

[Image description: Bright orange, blue, and red lines, structured in a manner suggesting stacked rectangular cuboids, overlap each other on a white background. White lines, also suggestive of cuboid structures, are arranged haphazardly over the colored lines, disrupting their order.]

The dual influences of her experience living abroad and a homecoming to a divisive political landscape emerged in the finished work. Some compositions are sparse and calm, while others so dense that one could feel the tension and turmoil of our human penchant to cluster and build armor against a perceived other. This undulation between density and layering mimics the act of constructing and deconstructing as something physical, but also as a concept. It digs into how we build realities of truth and fiction, as well as where the two intersect or diverge, positing questions about collective social connection.

The Photograph is Always Now, 2020, installation view, Diane Rosenstein Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, courtesy of the artist and Diane Rosenstein Gallery

[Image description: A gallery with white walls and a gray floor. Three artworks hang on the walls, while a long, narrow work runs along the floor, receding into the distance of the space. Over this piece hang eight silver rods, of different lengths and each with a light on the end, from the ceiling.]

Karapetian’s recent body of work, The Photograph is Always Now, coalesced all of the above into what is perhaps her most ambitious and expansive single installation in terms of its diversity of approach. It was conceived of with the architectural specificity of the Diane Rosenstein Gallery in Los Angeles as a driver in its layout: a long rectangle with multiple rooms, reminiscent of a church. While spurred by and containing documents of personal experiences, the realized artworks are a sort of reverent multiverse of the artist’s thought process around notions of memory and questions about a subjective reality.

the Longest Prayer, aka Child’s Pose (detail), 2020, plaster, MDF, organza, and unique chromogenic photograph, 420 x 30 x 1 ½ in., courtesy of the artist and Diane Rosenstein Gallery

[Image description: A long, narrow photographic print on shiny paper rests on a gray floor. The print runs horizontally and extends to the furthest edges of the image. It features a nude figure’s silhouette in yellow and brown. Their legs are underneath them and they are bent forward to stretch their arms out, palms placed down. The figure is repeated four times and each overlaps another.]

The photographs and sculptural pieces were chapters of a running narrative. The centerpiece, a stream of paper with a repeated outline of Karapetian’s nude body in yogic Child’s Pose, stretches across the floor at a monumental 420 inches in length. Two areas of the gallery were dedicated to the series Gesture of Memory and Stations, both consisting of unorthodox portraits of her father and his visitors taken in his hospital room. These ranged from intimately sized 8 x 10-inch to larger 20 x 24-inch unique gelatin silver photographs that were visual transcriptions of the artist’s hand splattering developer onto exposed photographic paper. The final images are incomplete and, in many cases, vaguely readable and Rorschachesque. Other sections of the exhibition displayed smeared blocks of color with diaristic, neon light-burned phrases such as “fuck it” and “I can’t find my way home.” And others still incorporated sculptural references to art historical iconography of works by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. Throughout, the palette of the artworks vacillated from warm to cool, while some were completely devoid of color, printed in black and white. Viewers developed a distinct sense that the artist had laid bare a deep well which we were invited to enter. In that moment, The Photograph is Now was her church.

Station 8, from the series Via Dolorosa, 2019, unique gelatin silver photograph, 24 x 20 in., courtesy of the artist and Diane Rosenstein Gallery

[Image description: A splatter on a white page. In the splatter is a black and white photograph of two people’s arms extending toward each other, clasping hands, which are in front of a window looking out onto a parking lot.]

With a spirit that doesn’t rest, Farrah Karapetian has continued to create throughout this unprecedented time of COVID-19. She’s voracious about living, constantly questioning and taking action. Karapetian’s ability to reflect upon, unearth, and explore the chasms of our place in the world are intrinsic to her being. That she is able to share and present it is both beautiful and mystical. To view Karapetian’s artworks is nothing like what you would expect photography to be, yet it is everything photography is becoming.

Chantal Paul is a San Diego-based curator of contemporary art.

![Lifesaver, 2015, unique chromogenic photogram, 56 ¼ x 40 in.[Image description: The white silhouette of a circular life preserver against a green, yellow, and brown background. Below the life preserver are forms suggesting bubbles in water.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e8235c414491577aa3f6148/1598296119234-J3FDOU8AIMQLIA82JETY/Karapetian_2015_Relief_Lifesaver.jpg)